Acts 15: Two Laws?

The Jerusalem Council (Acts 15:1-29) speaks directly to the relationship of Gentile believers and the Law of Moses. But does it also offer insights on the relationship between that Law and Jewish believers in Jesus? In his article, Was Paul Championing a New Freedom from—or End to—Jewish Law?, Dr. David Rudolph, a Jewish believer in Jesus, holds that Paul “regarded Jewish identity and law observance as a matter of calling and covenant fidelity.” And further that Paul “lived as a Torah-observant Jew and taught fellow Jews to remain faithful to Israel’s law and custom.” Rudolph’s conclusions introduce an interesting line of thought. Are there two laws—or at least two sets of obligations—on the Christian: one for the Gentile and one for the Jew? Are Gentiles to keep the commandments of Christ, while Jews are expected to keep both the Law of Moses and the commandments of Christ? An examination of Acts 15 offers some insight into these questions.

Two Groups

In Acts 15, we see two groups of Jewish believers in Christ arguing about a matter of theology. The first group, Group A, is teaching that Gentiles were to be circumcised and keep the Mosaic Law (a position we will label “C+ML” for short) to be saved. Group B disagrees. Michael Wyschogrod suggests that “both sides agreed that Jewish believers in Jesus remained obligated to circumcision and the Mosaic Law.”1 Is that a reasonable assumption about both sides? Moreover, do Jewish believers in Jesus, indeed, remain obligated to circumcision and the Mosaic Law?

If all Jewish believers in Jesus held that C+ML was no longer required of anyone, there would not have been a disagreement. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that Group A—those who taught that Gentiles should be required to keep C+ML—believed that Jewish believers were obligated to keep C+ML. Indeed, Group A promoted the idea that salvation came through keeping C+ML and, as such, Gentile believers needed to abide. But what about Group B? In Acts 15, we see them disagreeing that Gentiles were obligated to keep C+ML. Indeed, the quarreling Jewish believers convened a council to discuss this very issue. However, the council did not speak directly to whether the Jews were still obligated to keep C+ML. Therefore, Group B may have held that (a.) Jewish believers were required to do so, or (b.) no one is obligated to do so. The text can be read either way.

A Matter of Salvation

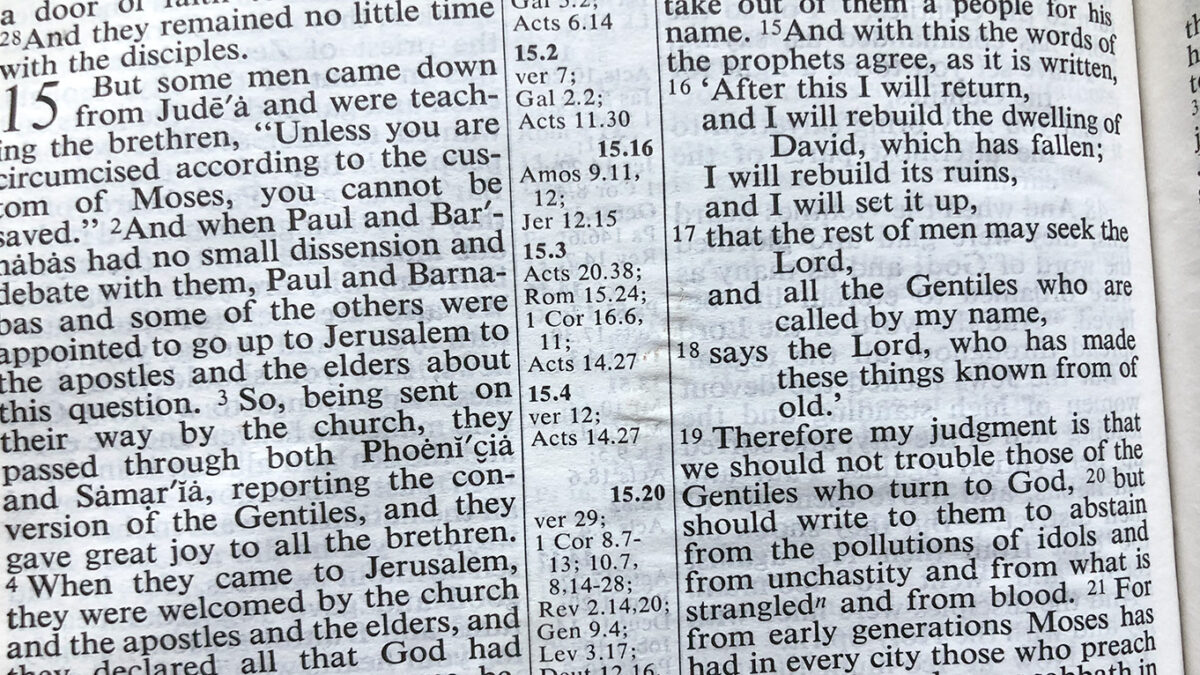

The Jerusalem Council passage begins with a question about salvation. “But some men came down from Judea and were teaching the brothers, ‘Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved’” (Acts 15:1, ESV). Concerning that teaching, “Paul and Barnabas had no small dissension and debate with them” (v. 2). So they headed to Jerusalem to discuss the matter among other apostles and church elders. Once gathered “some believers who belonged to the party of the Pharisees rose up and said, ‘It is necessary to circumcise them and to order them to keep the law of Moses’” (v. 5). Carrying forward the nature of the initial debate in verse 1, we can interpret the phrase “it is necessary” here in verse 5 as related to salvation. In other words, the question put before the council was, “Is it necessary to circumcise the Gentiles and require them to keep the law of Moses in order for them to be saved?”

This matter was then considered by the apostles and elders (v. 6), “and after there had been much debate, Peter stood up” (v. 7) and addressed the council. He related his own experience in sharing the Gospel with the Gentiles. In an apparent reference to the story of Cornelius (from Acts 10), Peter explained that God “bore witness to [the Gentiles] by giving them the Holy Spirit just as he did to us [Jews], and he made no distinction between us and them, having cleansed their hearts by faith” (vv. 8-9). In other words, God brought salvation to Gentiles who were not circumcised and did not keep the Law of Moses. They were saved by faith, not by keeping the commandments.

Peter continued his argument, saying, “therefore, why are you putting God to the test by placing a yoke on the neck of the disciples that neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear?” (“Disciplines” here presumably refers to the Gentile believers who were not keeping C+ML.) There is a Hebrew concept of a “yoke” as a teaching of a particular rabbi to which a student obligates himself. For example, Jesus said, “Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light” (Matt 11:29-30). Thus, we are not obligated to think Peter is using the phrase “yoke” to cast the Law of Moses in a negative light. But he does explicitly state that “neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear” the yoke of the Law.

Peter is referring to his contemporary Jewish brothers and sisters as well as their Jewish ancestors. In other words, all Jews. This sweeping statement brings to mind Romans 3 where Paul, citing Psalm 14:1-3 and Psalm 53:1-3, wrote, “as it is written: ‘None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one’” (Rom 3:10-12). Paul goes on to add, “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom 3:23).

Peter then comes to the culmination of his argument: “But we believe that we will be saved through the grace of the Lord Jesus, just as they will” (Acts 15:11). His statement reveals two details germane to our study. First, Jews and Gentiles are saved in the same way. Second, salvation does not come through keeping C+ML but rather through “the grace of the Lord Jesus.” Peter is echoing teachings found elsewhere in the NT:

For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.

Ephesians 2:8-9

Next, Barnabas and Paul tell of the signs and wonders they have seen God do through and among the Gentiles (v. 12). They offer evidence supporting Peter’s claim that God is bringing salvation to the Gentiles despite their lack of circumcision or keeping of the Mosaic Law. And then James, the head of the church in Jerusalem, speaks up. He quotes from Amos 9 and Jeremiah 12 to show that God’s calling of the Gentiles was foretold long ago (Acts 15:15-18). And then James issues a decision on the issue:

Therefore, my judgment is that we should not trouble those of the Gentiles who turn to God but should write to them to abstain from the things polluted by idols, and from sexual immorality, and from what has been strangled, and from blood.

Acts 15:19-20

In other words, James decided that the Gentiles should not be “troubled” with circumcision and the Mosaic Law as had been debated. Rather, they were to avoid four things. How are we to classify these four restrictions?

Interpreting them as a requirement of salvation would contradict the previous passages in which Peter taught that salvation comes through grace, not works. It would also contradict the passages in which we see God bringing salvation to Gentiles who were not keeping these four restrictions. Instead, they appear to have been given as guidance to the new Gentiles believers regarding how to live out their faith alongside their new Jewish brothers and sisters in Christ. There are two reasons for this interpretation.

First, the perspective of the Council as revealed in Acts 15:1-29 is that faith in Yeshua HaMashiach (Jesus the Jewish Messiah) was a Jewish belief. This was a debate between Jewish Pharisees and the Jewish apostles and elders, which occurred in Jerusalem, the geographical home of the Jewish people. The topic of discussion was what should be required of non-Jews who also want to follow Yeshua. Thus, it can be read as a sort of internal discussion among Jews who met to decide “what do we require of outsiders who want to join our faith”?

Second, James explains that he is giving the four restrictions because “from ancient generations Moses has had in every city those who proclaim him, for he is read every Sabbath in the synagogues” (Acts 15:21). In other words, he links the four restrictions with the widespread presence of Judaism. The point he is trying to make is not neatly explained. However, the interpretation that seems to make the most sense of this passage is that James was pointing out that the Gentile believers, no matter where they are located, are bound to come into contact with Jewish believers. Consider the following:

- The Jews at this council were discussing how to let Gentiles into the Jewish faith.

- The Jewish believers were people who had “from ancient generations” heard the Law of Moses read every Sabbath in the synagogue. It was not just their Law, it was in their cultural DNA.

- The council knew that new Gentile believers would be living and serving alongside Jewish believers. They would be worshipping the same God, gathering together to pray and break bread, etc.

- The four restrictions given by James were activities that would have been offensive to a Jew.

- These four restrictions were also activities that the average Gentile—who would have come from a pagan background—may not have realized would be offensive to a Jew. Gentiles would have known that things like murder and adultery were forbidden. But, these four would not have been so obvious.

Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the council’s concern in giving these specific restrictions was to promote unity between Gentile and Jewish believers. Indeed, this is a common theme throughout the NT. (See: Rom 12:3-8, 14:1-23; 1 Cor 8:7-13, Gal 3:23-29, 5:1-15; Eph 4:1-16; Phil 2:1-11; 1 Peter 3:8-22, etc.). Thus, James’ message in verses 19-21 could be reasonably paraphrased as:

Let us not make it difficult for the Gentiles who are turning to the Jewish God. Instead, let us offer them a few restrictions to help them keep the peace with their new Jewish brethren, who have been steeped in the Law of Moses for generations. Here are four guidelines that should be sufficient to keep relations agreeable between them.

Author’s suggested paraphrase of Acts 15:19-21

Additional support for this interpretation can be found in the way these restrictions are introduced in verse 19: “Therefore my judgment is that we should not trouble those of the Gentiles who turn to God.” The phrase “should not trouble” is rendered in other translations as “should not cause difficulties” (CSB) or “should not make it difficult” (NIV). The Greek word is parenochlein (Strong’s 3926) which means “to annoy.” James’ stated motivation of not wanting to trouble (or annoy, or cause difficulty for) the Gentiles lacks the force of a commandment or obligation. It speaks more to a matter of discretion in which a decision was made based on maintaining harmony or peace.

The way these requirements are referred to in the letter drafted by the council provides additional support for this interpretation:

For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay on you no greater burden than these requirements: that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols, and from blood, and from what has been strangled, and from sexual immorality. If you keep yourselves from these, you will do well.

Acts 15:28-29

They are referred to as “requirements” (ESV, CSB, NIV), or “necessary things” (KJV, LEB, NKJV, RSV), or “essentials” (NASB, NRSV). Yet, the closing statement of the Council’s letter on the matter—“If you keep yourselves from these, you will do well”—also appears to lack the force of a commandment or obligation. Especially since three of the four restrictions are dietary, and the teachings regarding food elsewhere in the NT indicate the dietary restrictions given in the Mosaic Law are no longer binding (Mark 7, Rom 14, etc.). Indeed, N. T. Wright, in a comment on Romans 14, notes that “Paul did not himself continue to keep the kosher laws, and did not propose to, or require of, other ‘Jewish Christians’ that they should, either.”2

Therefore, these four restrictions appear to have been given neither as a matter of salvation nor as a commandment or obligation of obedience. Instead, they seem best understood as a directive for maintaining harmony and unity in the nascent Christian church.

Summary

Acts 15 partially answers our “two law” question. It reveals that neither Jews nor Gentiles are required to be circumcised or keep the Mosaic Law as a matter of salvation. We are all saved the same way: by grace through faith and not by works (Eph 2:8-9). Additionally, the council’s decision reveals that Gentiles are not required to keep C+ML as a matter of obedience.

This leaves one question unanswered: Are Jewish believers in Jesus obligated to keep circumcision and the Mosaic Law? Acts 15 does not directly speak to this question. If the answer is yes, it would mean that, although there is a single way to salvation, Jewish and Gentile believers are to walk out their obedience differently. But, alas, we would need to expand our search to other NT passages to find a sufficient answer to that question.

[1] Michael Wyschogrod, Abraham’s Promise: Judaism and Jewish-Christian Relations, ed. R. Kendall Soulen (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, (2004), 194.

[2] N. T. Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness of God (Minneapolis: Fortress, (2013), 359.

Barry Jones

If some of Jesus’ pre-crucifixion ministry had fulfilled an OT prediction that Gentiles would get saved (Matt. 12:15-21, “in his name will the Gentiles hope…”), then before he died, Jesus had either expressed or otherwise manifested by his actions what he required male Gentile followers to do to get saved.

That being the case, why doesn’t Acts 15 have the apostles quoting Jesus’ words or acts to refute the Judaizers?

If Jesus dealt with male Gentile followers and never required them to be circumcised, why aren’t the apostles appealing to this obviously final authority to put the controversy to rest?

is bible inerrancy such an untouchable icon in your faith that you will literally do anything possible to retain your belief that the original apostles and Paul agreed with each other about how to answer the Gentile-circumcision question?

I’ve read some conservative inerrantist commentators who allow that Paul may possibly have flouted the eating prohibitions expressed in the apostolic letter resulting from the Council of Jerusalem (15:29), so I’m not understanding why inerrantists would rather die than admit there might be some genuine doctrinal disagreement between Paul and the original apostles. It isn’t like the alleged doctrinal harmony between them and Paul is so completely obvious that only fools would deny it.

Early Christian sources say James was held in very high esteem by the Jewish people. Given how obstinate they were in requiring Gentiles to be circumcised to be in covenant with YHWH (Exodus 12:48), what’s reasonable is the conclusion that James agreed with them 100% on that matter, even if he was also a Christian. What’s not reasonable is the trifle that the Jews would think so highly of a Christian apostle who viewed circumcision as unnecessary for Gentiles to be in covenant with YHWH.

Then we have Acts 21:18-24, informing us that James was one of the leaders of a Jewish faction of the church who were “zealous for the law” and scandalized by the thought that Paul would relax the circumcision laws for people living outside of Jerusalem. What’s reasonable is the inference that the laity strongly upheld circumcision because their leader James also strongly upheld it. What’s unreasonable is the trifle that James could be the leader of a circumcision-demanding faction of the Christian church while he himself thought the rite unnecessary. Sort of like a fundamentalist church today that is being pastored by a liberal. Saying there was doctrinal conflict between Paul and the original apostles might possibly be wrong, but it most certainly is not unreasonable.

Then we have Paul in Galatians 2:12 saying Peter acquiesced to the Judaizer view when “men from James” came to town, when in fact Peter had intimate knowledge of James, and had those “men from James” espoused a more conservative view on the Gentile question than James did, Peter would have known they were misrepresenting James, and would no more have acquiesced to their views than you might acquiesce to Mormon views that you currently think misrepresent Jesus. No, Peter acquiesced to their view and ceased his table fellowship with Gentiles because he knew they CORRECTLY represented James’ position. So again James is presented as adopting a Judaizer position.

Then in the next verse Paul says his own right hand man Barnabas (personally selected by the Holy Spirit, no less, Acts 13:2) eventually took the Judaizer position against Paul on the matter of table fellowship (Galatians 2:13).

Then in the next verse Paul accuses Peter of requiring Gentiles to live as Jews, which is of course, exactly what a Judaizer would require.

In fact by Paul’s own admission the entire Galatian church decided the Judaizer gospel was true and consequently abandoned his gospel (Galatians 1:6-9).

So what I don’t understand is why inerrantists jump around acting like crediting the original apostles with the Judaizer viewpoint is akin to ascribing the polytheist viewpoint to Jesus.

R. L. Solberg

Thanks, Barry! I think the fact that the apostles convened a council in Jerusalem to discuss the Judaizer question shows (a.) there was doctrinal conflict between the early believers (Acts 15:2), and (b.) this was an issue they had not yet dealt with as a church. At least not in great depth. Two groups of Jewish believers in Jesus found themselves in such a sharp debate that they gathered the apostles and elders to discuss the issue. Now that Jesus had been crucified and resurrected and the New Covenant had been inaugurated, what did that mean for the Law of Moses and Gentiles? It was a paradigm shift for the early Jewish believers in Jesus and they were trying to find their way. I believe God placed the record of this council in Scripture to show future believers (a.) what the apostles ultimately decided after debating this important issue (under the guidance of the Holy Spirit), and (b.) to model for us how we as a church ought to handle doctrinal disagreements when they arise.

Mitch Chapman

Rob, For clarification, what is your definition of the theologically charged word Judaizer? Also, was there really ever a ‘church’ in the 1st Century that ANY of the Disciples and or Apostles attended? If so, what was the name/names?

Bezalel

Circumcision is still for jews wether we believe in Yeshua or not. Acts 15 is Clear! Jews are to remain Jews and Gentiles are to remain Gentiles. I believe You are wrong saying circumcision is not required for jewish believers. it’s NOT required for GENTILES. scriptures is clear. for example…Acts 21:20-25

Paul Visits Jacob “James”

17 When we arrived in Jerusalem, the Lord’s followers gladly welcomed us. 18 Paul went with us to see Jacob “James” the next day, and all the Ecclesia leaders were present. 19 Paul greeted them and told how God had used him to help the Gentiles. 20 Everyone who heard this praised God and said to Paul:

My friend, you can see how many tens of thousands of our Jewish people have become followers! And all of them are eager to obey the Law of Moses. 21 But they have been told that you are teaching JEWS who live among the GENTILES to disobey this Law. >>They claim that you are telling them not to circumcise their sons or to follow our customs.<>REPORTS ABOUT YOU ARE NOT TRUE << =(telling jews not to circumcise) .They will know you do obey the Law of Moses.

25 Some while ago we told the GENTILE followers what we think they should do. We instructed them not to eat anything offered to idols. They were told not to eat any meat with blood still in it or the meat of an animal that has been strangled. They were also told not to commit any terrible sexual sins.[c]

A Jew is to circumcise and remain a Jew and a Gentile is not to become a jew and remain a gentile= KEEP YOUR ETHNICITY. Messiah never came to erase ones ethnicity. He came to bring unity in faith with our differences.and allows freedom of expression.

example..Look at the bag ofJelly babies (I like the kosher ones btw). All different colours all in one bag. They all look different but in one bag. Same idea of all different people in one faith/belief. God loves variety. Hope this helps Shalom.

Mitch Chapman

Bezalel,

You are responding to a staunch western Christian who has continually demonstrated by his infrequent responses that he doesn’t grasp THE REAL GALATIANS ISSUE!

The so called theologian hasn’t used any real hermeneutics, but continues to make it up as he sees fit through a 2023 lens not through the culture and context of when Galatians was written. He will quote those that agree with him and through his eisegeises philosophy continually remain anachronistic.

Like many who have soundly refuted him, you will likely not receive a reply other than “that’s very interesting” followed by his jaundiced philosophy with additional western Christian verbiage.

R. L. Solberg

Hello, Mitch! I have to say I’m a bit surprised by your personal attacks. You are a follower of Jesus, no? Bearing false witness is quite a serious thing in God’s eyes. It’s especially problematic when a follower of Christ posts a comment to a third party for the sole purpose of slandering a fellow believer in Christ.

Also, I should think you’re aware that the frequency of one’s responses to angry, confrontational critics has no bearing on one’s ability to grasp the meaning of biblical texts. You seem like quite an intelligent man, so your comment to that effect is a bit puzzling.

Shalom, Rob

Bezalel

Shalom, it would be great if you could comment on what I said. I hope you are well. shalom in Yeshua Ha mashiach.

R. L. Solberg

Hello, Bezalel! I respectfully disagree with your conclusion that circumcision is required for Jewish believers in Jesus. I do not believe God has two sets of standards for His people. The NT teaches that circumcision as a ritual is not required of any follower of Jesus. It is permitted, of course. But not required.

The rite of circumcision is actually introduced twice in the Torah. First with Abraham in Genesis 17, and then again when we get to Moses, where it’s given additional significance in Leviticus 12 (Lev 12:1-4). For a person to be circumcised under the law of Moses, it included a commitment to the Sinai covenant and an obligation to keep the Mosaic law. So circumcision meant a lot more under Moses than it originally did back in the days of Abraham. And here’s where things get interesting in terms of the law.

In the early days of the Christian church, the Judaizers were teaching circumcision pretty strongly. It was a prominent identity marker for followers of the God of Israel. And Paul’s admonition about circumcision in Galatians 5 reveals that things had changed dramatically under the New Covenant:

Circumcision was a requirement under Moses. And Paul calls it a yoke of slavery that undermines the value of what Jesus did for us. He says, “if you accept circumcision, Christ will be of no advantage to you” (Gal. 5:2). The acceptance of the Mosaic rite of circumcision as a matter of obedience or righteousness is an insult to the work of Christ. And he adds in verse 3, “every man who accepts circumcision is obligated to keep the whole law” (Gal. 5:3). And in the next verse he uses wordplay on the idea of circumcision, adding, “You are severed from Christ, you who would be justified by the law.” So he’s specifically talking about circumcision when it’s undertaken in a ritual sense out of obedience to the law of Moses. And to drive his point home, Paul writes a few verses later, “For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision counts for anything, but only faith working through love” (Gal. 5:6). And then once more in chapter 6 for good measure, “For neither circumcision counts for anything, nor uncircumcision, but a new creation” (Gal. 6:15).

In the Torah, ritual circumcision was a command of Yahweh to be undertaken on the eighth day after birth. In the New Testament, because of the work of Christ on the cross, ritual circumcision is a yoke of slavery that undermines the value of what Jesus did for us. Circumcision has served its God-ordained purpose and is no longer required.

Shalom, Rob

Mitch Chapman

Rob, There you go again with your Western church mindset and anachronistic terms. There was NO church in the 1st Century and you once again missed the point of not only the historical and cultural context of Galatians but also missed the mark regarding Acts 15.

Time and time again your errors have been called to your attention, and you choose to remain with your church doctrine and definitions as well as your Western church theology and terminology!

You retain very shoddy hermeneutics which remains your philosophical eisegeises.

Shabbat shalom from Ddwaniro, Rakai District, Uganda

Barry Jones

“There was NO church in the 1st Century”

——-Does that mean you think the 2nd century is the earliest point at which Matthew’s gospel was published? He has Jesus mention “church” in Matthew 16:18 and 18:17.

Mitch Chapman

Barry,

Why not do your homework before asking your questiin?

What is the Greek word rendered in English as church?

is this Greek word found in LXX, thecGrekntranslation of the Hebrew Scriptures, TaNaK?

If so what’s the Hebrew source word?

This friend, is a basic introduction into hermeneutics.

R. L. Solberg

I’m going to level with you, Mitch. I’m a busy man. I have a number of projects underway and it’s a challenge to balance my time between those projects and interacting with viewers/readers across my blog and social media channels. I try to be wise with my time because as Churchill famously said, “You will never reach your destination if you stop and throw stones at every dog that barks.” As a result, I tend to spend my time where there is a legitimate interest in exchanging ideas because that brings the most benefit to all parties involved. Conversely, I tend to avoid angry, confrontational commenters who resort to ad hominem arguments and enjoy slinging mud. Hence, my dearth of replies to your comments.

Regarding your most recent post: Of course there was a church in the 1st century! Jesus spoke of it, Acts records it’s growth, Paul wrote of (and to) many churches, and Revelation mentioned many churches.

Blessings,

Rob

Mitch Chapman

Rob, Im not at all angry but extrenely disappointed how you a seemingly inteligent person, and so called “theologian, apologist, author, and bible professor” takes English translations from Greek and concludes there was anything called a church in 1st Century, and a biblical testament.

Using your philosophic esigeisis and anachronistic terminology, do you also conclude easter in Acts 12:4 is OK too?

This is a form of KJV onlyism.

NOW you’re leveling with me indicating anything previous you were not? Hmm

Any serous bible student who isn’t a theologian, aplogist, author and or bible professor would ask since there is a Greek word does it appear anywhere in LXX, if not, the conclusion would be its taken from the Greek spoken from the 1st Century. However, if it appears in LXX, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, TaNaK, there must be an original Hebrew word.

What is the Hebrew translated into the Greek ekklesia, church? What is the Hebrew translated into Greek diathake, testament? What is the Hebrew translated into Greek pascha, easter?

Don’t even try to play the Strongs card as any serious bible student knows the context determines the definition and Strongs provides the root meaning..

Let’s face it, for you to seriously address any of the legitimate questions and or statements responding to your jaundiced western church dogma would threaten your minustry and derail it.

R. L. Solberg

Understood, Mitch. And, for the record, I have no problem with you being disappointed in me. But I’m a little concerned you might not understand how the translation process works. Either that or the point you’re trying to make is overly imprecise.

You stated “There was NO church in the 1st Century,” and you used the English word “church.” I responded by pointing out a number of places the word “church” is used in the English translation of the NT. (eg., “And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Matt. 16:18). “But Saul was ravaging the church, and entering house after house, he dragged off men and women and committed them to prison” (Acts 8:3).)

And, of course, “church” is the English translation of ἐκκλησία. In other words, what English speakers call “church,” Greek speakers call ἐκκλησία — refering to a gathering or assembly of believers in Jesus. So was there a church in the first-century? Of course. I’m confused how you could come to any other conclusion. Unless you’re using a special definition of the word “church”?

RLS

Bezalel

I disagree Rob. I really do.

Acts 15:1-29 is Very CLEAR. Circumcision is NOT for who? GENTILES!

4 things are given for Gentiles. If you don’t like those 4 Things and claim its different standards then respectfully it’s your own issue. I don’t know where you are going with claiming “different standards”. Were Jews given those 4 requirements? and Were Jews told not to circumcise? in Acts 15? NO.

These 4 requirements were given for unity. And still pretty much apply today in my knowledge. If you don’t like them and claim its different standards then it’s up to you. who’s forcing you? it’s clear what it says to me between the two ethnicities coming together.

Does it mean jews are better than Gentiles or the other way round no.

Circumcision IS indeed for Jews and NOT for Gentiles. these are Not different standards in worship. Ethnicity are NOT to be erased.

A jew that doesn’t circumcise is no longer a jew. he’s a gentile. As gentiles are called the uncircumcised in flesh. Paul was sent to the uncircumcised Gentiles! and Peter and Jacob/James were to the circumcised =Jews because they are circumcised and jews still circumcise.

Circumcision Is for JEWS as given to Abraham’s physical descendants Before the sinai covenant.. it’s very clear.

Jacob/James and the elders made it very clear GENTILES don’t have to. They clearly say who don’t have to.

There does it say jews don’t have to?? . they even said to Paul they found the rumours about him is not true that he taught jews not to circumcise their kids and forsake the customs. I posted the scriptures before. Sorry I listen to scripture. And no, it’s not different standards at all, its two different cultures being brought together in what was given to them and how to be in unity with their ethnicities and different cultures in one faith.

Again Read, Acts 21:21-25 is clear as day.

20 When they heard this, they praised God. Then they said to Paul: “You see, brother, how many thousands of Jews have believed, and all of them are zealous for the law.

Acts 21:21 ! >>They have been informed that you teach all the JEWS who live among the GENTILES to turn away from Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or live according to our customs!<> there is no truth in these reports about you<>They have been informed that you teach all the JEWS who live among the GENTILES to turn away from Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or live according to our customs!<> there is no truth in these reports about you<<, but that you yourself are living in obedience to the law!

Conclusion: As far as I can see, The scriptures are clear. Circumcision and jewish observances are NOT required of GENTILES. They are to be themselves as Gentiles. so yes the "Hebrew roots movement" are misguided. ACTS 15 is clear as a Diamond.

Shalom from jewish Saint.

R. L. Solberg

Thanks, Bezalel! I agree that the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15 determined that circumcision was not required of Gentiles and that those 4 restrictions were given as a matter of unity in the early church. I also agree that there are no different standards in worship and that ethnicity is not to be erased.

The biblical definition of a “Jew” is a person descended from Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. It’s an ethnicity. And Jews are not born circumcised. Circumcision is a ritual commanded under the Mosaic law performed on a male at eight days old. That state of one’s foreskin has no bearing on one’s ethnicity. Indeed, if a Jewish person who is not circumcised ceases to be Jewish and becomes a Gentile, then there have never been female Jews in history.

Paul’s words in Galatians about circumcision, which I mentioned above, are given without respect to ethnicity. “Look: I, Paul, say to you that if you accept circumcision, Christ will be of no advantage to you. I testify again to every man who accepts circumcision that he is obligated to keep the whole law” (Gal. 5:2–3). Paul makes no distinction between Jews and Gentiles. The NT teaches that circumcision is not required of any follower of Jesus, although it is certainly permitted. I don’t believe God has two standards of obedience, one for Jews, and one for Gentiles.

As for Paul’s actions in Acts 21, I believe they are best understood in light of 1 Cor. 9:19–23.

Shalom! Rob

Bezalel

I agree with a lot of what you said expect a few parts.

Answering what you said here: The biblical definition of a “Jew” is a person descended from Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. It’s an ethnicity. And Jews are not born circumcised. Circumcision is a ritual commanded under the Mosaic law performed on a male at eight days old. That state of one’s foreskin has no bearing on one’s ethnicity.

Sorry again I strongly disagree… It was Given under Father Abraham BEFORE Moses and the law at Siani. And guess what, John 7:22 Refutes your above Statement. John 7:22 NLT -But you work on the Sabbath, too, when you obey Moses’ law of circumcision. (Actually, this tradition of circumcision began with the patriarchs, LONG BEFORE the law of Moses.)

So guess what, it’s to do with Abraham.

And replying to what you said here: “Indeed, if a Jewish person who is not circumcised ceases to be Jewish and becomes a Gentile, then there have never been female Jews in history.”

My answer: there are different requirements for male and female on what makes one jewish it’s a weak argument you know the requirements for men/Boys in jewish culture. if one is Not circumcised as a male he is NOT a jew. thats why there were people trying to get foreskins sewn back on to hide that FACT that they were Jewish.

Do you know about epispasm? That epispasm was fairly widespread among Jews also seems evident from 1 Maccabees 1:11-15, where we are told that some built a gymnasium in Jerusalem and “made themselves uncircumcised.”

1 Corinthians 7:18 -19(ASV)

Was any man called being circumcised? let him not become uncircumcised.=Jews and Epispasm.

Hath any been called in uncircumcision? let him not be circumcised.

=Gentiles don’t need to become jews.

so how would they become a jewish- proselyte?=CIRCUMCISION. Esther 8:17. another example. Hence the debate should gentiles become jews first to believe in yeshua? Acts 15 settled it. NO.

Now people want jews to become Gentile to follow Yeshua. NOT in My house.

(Rom. 2:28-29) is between two Jews. Which is the real jew? And he’s not saying NOT to Circumcise he’s saying where the true one is. Again Acts 21 he’s not teaching not to circumcise jewish children . He’s pointing back here also..Deuteronomy 30:6

AND here Jeremiah 4:4. Guess what were they physically circumcised also? YES.

Answering what you said here: Paul’s words in Galatians about circumcision, which I mentioned above, are given without respect to ethnicity.

My answer: No he’s He’s talking to Gentiles here in Galatia and warning THEM not to..

“Look: I, Paul, say to you that if you accept circumcision, Christ will be of no advantage to you. I testify again to every man who accepts circumcision that he is obligated to keep the whole law” (Gal. 5:2–3).

Paul makes no distinction between Jews and Gentiles.

My answer: He’s taking to gentiles sepcifically, no jew is mentioned..

Example , Romans 1:16=whom is mentioned?

1 Corinthians 12:13= Whom is mentioned?

Acts 15:23 =Whom is mentioned?

Acts 21:21=Whom is mentioned?

Who are the Galatians again sorry? He’s an apostle to THE GENTILES.

Paul did NOT teach jews not to circumcise their kids. the scriptures SAY SO.

it makes it clear in Acts 21.

Reminder… Acts 21:21

They have been informed that you teach all the JEWS who live among the GENTILES to turn away from Moses, telling them NOT to circumcise their children or live according to our customs.

Acts 21:24

Take these men, join in their purification rites and pay their expenses, so that they can have their heads shaved. Then everyone will know there is NO TRUTH in these reports about you, but that you yourself are living in obedience to the law. = so (Gal. 5:2–3). cannot contradict Acts 21:-24, if you are saying he’s talking to Jews too. he’s clearly talking to gentiles.

You said: The NT teaches that circumcision is not required of any follower of Jesus.

Again I respectfully disagree, the text makes it clear who does and who doesn’t circumcise. we cannot add and take away.

Acts 15 Is very Clear and Acts 21 is very clear as a Diamond. it says specifically Circumcision is not for=Gentiles.

So yes Circumcision is NOT required for GENTILE Believers written in Black and white. And we can agree on that.

What about Genesis 9:13-16?= Does this still apply? YES.

So Circumcision IS indeed for JEWS I’m sorry this is what I see in scripture I cannot see where it says JEWS don’t do this.

You said: I don’t believe God has two standards of obedience, one for Jews, and one for Gentiles.

My answer: well, obedience is something to obey

Dictionary

obedience /ō-bē′dē-əns/

noun

The quality or condition of being obedient.

The act of obeying.

A sphere of >ecclesiastical < authority.

So then why were 4 things given to gentiles to OBEY that became written down in a letter then sent by the ecclesiastical authority? isn't obedience in a different way to bring unity? and are these same 4 things given not jews? No. Gentiles had to live by those things given and still suppose to in my eyes when around us jews . Sorry.

It was a different requirement or "Standard" but for unity.

And as you said yourself in your summary here:

This leaves one question unanswered: Are Jewish believers in Jesus obligated to keep circumcision and the Mosaic Law? Acts 15 does not directly speak to this question.

My answer: No Acts chapter 15 doesn't speak on it but i believe Acts Chapter 21 does. it's clear as Day.

So my conclusion: With what is written and the resolution written in Acts 15 and Acts 21, Are Jews to still Circumcise? in my eyes from what I can see =YES

Are Gentiles? from what I can see=NO.

Does physical Circumcision save? =NO.

Are we all saved in the same manner? wether Jew or gentile? YES!

Our customs /cultures and identity remain. We are to be unified in them. Do I do Christmas and easter? NO I am not a gentile. Do you do Shabbat and passover? maybe not. Are we talking out our faith exactly the same in every detail for example observances, holidays etc? NO. Romans 14:5 for example.

Nowhere in the New Testament does it say for Jews not to circumcise their sons! Acts chapter 21!

Anyway Great speaking with you shalom( from a Jewish Saint).

Bezalel

Here’s something for you Rob.

I A jewish believer with some other jews where I am consider ourselves Nazarene Jews. and Yes its biblical. we are followers of the way rather than modern “christianity”.

If you read your bible and read Mathew 2:23 and Acts 24:5 it will make sense. Nazarenes (Jews) and Christians (gentiles) are two different groups.Hence why me and you cannot agree on circumcision and I stay strictly with the decision of Jacob (James) and our elders in Acts 15. about the matter.

Here, Read these from “church” history recordings about the Nazarenes also and look into them. Shalom.

4. Epiphanius.

When we come to Epiphanius (born and raised in Palestine), we finally get a by-name mention of the Nazarenes. His Panarion (generally known as the Refutation of All Heresies) was written during the period 374-376. Panarion 29 is a rather extensive treatment of his sources and data on the Nazarenes, and the salient facts about them are listed below:

a. The use both the Old and New Testaments, without excluding any books known to Epiphanius (7,2):

“For they use not only the New Testament but also the Old, like the Jews. For the Legislation and the Prophets and the Scriptures, which are called the Bible by the Jews, are not rejected by them as they are by those mentioned above [Manicheans, Marcionites, Gnostics]. “

b. They have a good knowledge of Hebrew and read the OT and at least one gospel in that language (7,4; 9,4):

“They a good mastery of the Hebrew language. For the entire Law and the Prophets and what is called the Scriptures, I mention the poetical books, Kings, Chronicles and Ester and all the others, are read by them in Hebrew as in the case with the Jews, of course.”

“They have the entire Gospel of Matthew in Hebrew. It is carefully preserved by them in Hebrew letters.”

c. They believe in the resurrection of the dead (7,3):

“For they also accept the resurrection of the dead “

d. They believe that God is the creator of all things (7,3):

“…and that everything has its origin in God”

e. They believe in One God and His Son Jesus Christ (remember the patristic defn. of divine Son!) (7,3; 7,5):

“They proclaim one God and his Son Jesus Christ.”

“Only in this respect they differ from the Jews and Christians: with the Jews they do not agree because of their belief in Christ, with the Christians because they are trained in the Law, in circumcision, the Sabbath, and the other things.” (Note how significant this is–they did NOT differ from Christians in Christology! This demonstrates a High Christology on their part!).

f. They observe the Law of Moses (7,5; 5,4; 8,1ff)

“Only in this respect they differ from the Jews and Christians: with the Jews they do not agree because of their belief in Christ, with the Christians because they are trained in the Law, in circumcision, the Sabbath, and the other things.”

“By birth they are Jews and they dedicate themselves to the Law and submit to circumcision.”

g. They are hated by the Jews and are officially ostracized in the synagogue prayer–probably the birkat ha-minim (9,2-3):

“However, they are very much hated by the Jews. For not only the Jewish children cherish hate against them but the people also stand up in the morning, at noon, and in the evening, three times a day and they pronounce curses and maledictions over them when they say their prayers in the synagogues. Three times a day they say: ‘May God curse the Nazarenes.’ For they are more hostile against them because they proclaim as Jews that Jesus is the Christ.”

[Ray] Pritz summarizes the data from the most important section of Epiphanius (Panarion 29,7) [NT:NJC:44]:

“The data in this section present us with a body in every way ‘orthodox’ except for its adherence to the Law of Moses. If we remember that the Jewish Church of Jerusalem also kept the Law through the period covered by the books of Acts, then we have a picture of the earliest Jewish Christian community…The picture is not full, certainly, but what we are given in very way confirms the identity of the Nazarenes as the heirs of the earliest Jerusalem congregation.”

Thus, Epiphanius is our first source on the Nazarenes, and he describes them as decidedly orthodox in all matters (including the deity of Christ), except that of observance of Jewish customs.

5. Jerome

Jerome is one of our more important sources, especially since he quotes from Nazarene written works. Let’s look at his testimony about them first.

“They believe in Christ, the Son of God, born of Mary the Virgin, and they say about him that he suffered under Pontius Pilate and rose again” (Epis. To Augustine, 112,13)

From their commentary on Isaiah at 29.17-21, the Nazarenes accuse the Scribes and Pharisees that they ‘made men sin against the Word of God in order that they should deny that Christ was the Son of God’

Also from the commentary, at 31.6-9: “The Nazarenes understand this passage in this way: O sons of Israel, who deny the Son of God with such hurtful resolution’”

Pritz summarizes [NT:NJC:55]:

“According to Jerome, then, Nazarene Christology is basically what we have noted previously, a belief in the divine origins and virgin birth of Jesus in accordance with accepted doctrines of the great Church. Here we also see an express avowal of Jesus’ death and resurrection.

In Jerome’s commentary on Isaiah, he gives 5 citations or comments from a Nazarene commentary on the book. These five selections preserve some interesting data about the group:

1. (on Isaiah 8.14): “The Nazarenes, who accept Christ in such a way that they do not cease to observe the old law, explain the two houses as the two families, viz. Of Shammai and Hillel, from whom originated the Scribes and the Pharisees.” [In this passage, Jerome does not even hint at censure of the Nazarenes, but rather uses them as a source. The data in the subsequent Nazarene discussion of the Shammai and Hillel show that they had significant antipathy toward the rabbis.]

2. (on Isaiah 8.20-21). “For the rest the Nazarenes explain the passage in this way: when the Scribes and Pharisees tell you to listen to them, men who do everything for the love of the belly and who hiss during their incantations in the way of magicians in order to deceive you, you must answer them like this…” [Note again the strong anti-rabbinical polemic, and the appeal to scripture–not halakah–for proof.]

3. (on Isaiah 9.1-4). “The Nazarenes, whose opinion I have set forth above, try to explain this passage in the following way: When Christ came and this preaching shone out, the land of Zebulon and Naphtali first of all were freed from the errors of the Scribes and Pharisees and he shook off their shoulders the very heavy yoke of the Jewish traditions. Later, however, the preaching became more dominant, that means the preaching was multiplied, through the Gospel of the apostle Paul who was the last of all the apostles. And the Gospel of Christ shone to the most distant tribes and the way of the whole sea. Finally the whole world, which earlier walked or sat in darkness and was imprisoned in the bonds of idolatry and death, has seen the clear light of the Gospel.”

This is a crucial passage and Pritz’ careful statement brings out the import and implications [NT:NJC:64-65]:

“Let us note once again the polemic against Scribes and Pharisees and the Jewish traditions. The two most significant things about this excerpt from the Nazarene work are its positive view of Paul, and the refusal to bind Gentile Christians to keeping the Law. We see here that the Nazarene view of Paul’s mission corresponded very closely to that of Paul himself (Gal 2.2-9). In none of the remains of Nazarene doctrine can one find a clear rejection of Paul or his mission or his message. This, of course, is quite the opposite of what we usually hear described as ‘Jewish Christian,’ which almost by definition opposes itself to Paul. What we have here, then, is an endorsement of Paul’s mission to the Gentiles. This spreading of the Gospel to the Gentiles was, according to the Nazarenes, a natural, even a glorious development. One is often led to expect a sort of bitterness on the part of the Jewish Christians that they were swamped, their position usurped by the Gentile Church. But here we find only a positive reaction to the flow events.”

Needless to say, this data about the pro-Pauline and high-Christology Nazarenes would not sit well with Jochen’s disputant!

4. (on Isaiah 29.20-21): “What we have understood to have been written about the devil and his angels, the Nazarenes believe to have been said against the Scribes and the Pharisees…who made men sin against the Word of God in order that they should deny that Christ was the Son of God” [We have referred to this passage earlier, in pointing out that the Nazarx held to a divine Sonship, of patristic content.]

5. (on Isaiah 31.6-9): “The Nazarenes understand this passage in this way: O Sons of Israel, who deny the Son of God with a most vicious opinion, turn to him and his apostles…” [Note the ‘Sonship’ Christology and the evangelistic appeal to their people.]

The data from Jerome is significant for many reasons, but not the least of which is that it contains the self-testimony of the Nazarenes. The excerpts from their Commentary on Isaiah show an incredibly ‘orthodox’, evangelistic, and universal outlook on God’s actions in the world. As such, the best data we have indicates that the Nazarene ‘sect’ was unquestionably mainstream ‘Christian’ and exalted Jesus as the pre-existent and absolutely unique Son of God (in the Patristic understanding).

6. Filaster

Filaster was a bishop who wrote his work (Book of Diverse Heresies) roughly at the same time of Epiphanius. He discusses 156 heresies or heretical teachers (some very borderline heresies, to be sure!), but omits the Nazarenes! Pritz points out this amazing fact, before analysing Filaster sources [NT:NJC:71]:

“His diversarum haereseon liber was written in 385…and covered 156 heresies or heretical teachings. The Jewish Christian Nazarene sect is not mentioned by Filaster. This fact naturally causes one to wonder why the Nazarenes were omitted from so extensive a work when Filaster went so far as to condemn even those who differed from the Church only in their belief that the stars occupied fixed positions in the heavens (as against the then-current teaching that God set them in place every evening).”

After analyzing Filaster’s sources [Hippolytus, drawing from Ireneaus, drawing from Justin and/or Theophilus of Antioch], Pritz comes to the following position [NT:NJC:75]:

“Where does all this leave us? In tracing Filaster’s literary heritage back to near its beginnings, we may at least hazard the suggestion that the earliest hersiographers did not include the Nazarenes for the simple reason that they did not consider them heretics. This, of course, was not true of the offshoot Ebionites, who even by the time of Irenaeus (and earlier Justin, who, however, does not mention them by name) had been recognized as heretics. If we extend this logic into the late fourth century, we arrive at this important conclusion: the lack of polemic against the Nazarenes until the fourth century does not show that they were a later phenomenon; rather, it shows that no one until Epiphanius considered them heretical enough to add them to older catalogues. The very existence of Filaster’s contemporary anti-heretical work with its omission of the Nazarenes in accord with his inherited tradition lends weight to the suggestion that Epiphanius is solely responsible for their inclusion in his own heresiography, and this despite the fact that he could not deny their ancient beginnings. While each author used the lists of his predecessors and added to them where he saw fit, no one until Epiphanius felt it necessary to include the Nazarenes, even though they had existed from the earliest times and their gospel was known.”

Unfortunately, this scenario changed with Augustine. He accepted the verdict of Epiphanius, and his authority swayed the rest of the church after that. The confusion of Nazarene and Ebionite in Epiphanius is still operative. So Pritz (NT:NJC:82]:

“The most important conclusion of this chapter is that the Nazarenes were not mentioned by earlier fathers not because they did not exist by rather because they were still generally considered to be acceptably orthodox. The history of the Nazarene Jewish sect must be clearly distinguished from that of the Ebionites. Once Epiphanius failed to do so, he introduced a confusion which continues to the present day.”

Summary of the data from the Church Fathers:

The Nazarene sect is a very orthodox group of believers. They hold to a very high Christology (i.e. virgin birth, pre-existence, more-than-man, divine sonship, deity of Christ). They have a high regard of Paul and the ministry to the Gentiles. They are both in polemic with and witnessing to, the Jewish people in mainline Palestine. They accept the Tanakh/OT and New Testament. They were not considered heretical until the mistake of Epiphanius (who confused them with the Ebionites).

I really hope this will open your eyes check the sources. I’m not a western “christian” protestant. I am a Jewish NAZARENE. I have more than” 66″ books smilier to the Ethiopic canon or Orthodox Canon which includes 1Enoch. Please see what I wrote on your other section the temple being rebuilt. Shalom in Yeshua

Shalom.

Mitch Chapman

Hi Rob, Greetings in Messiah from the Pearl of Africa, Uganda

That’s interesting as slander is defined as “the utterance of false charges or misrepresentations which defame and damage another’s reputation.

https://www.merriam-webster.com › …

When did being reproved become slander?

Regardless, why not attempt refuting line by line everything that only just now received your undivided attention

Bezalel

check my comments. what is your views?

Mitch Chapman

contact me directly via email

mcchap0@gmail.com or WhatsApp

+256 741 774119