Is Evil a Problem to Be Solved?

Another day, another mass shooting. At least this one ended relatively well for the innocent parties involved. My soul is weary of all the violence and unrest going on in my country. And the truth is that this problem is much bigger than the current cultural landscape of the USA. Any sane person knows there is something very wrong with human beings as a species. Man’s inhumanity to man* is as old as mankind itself. According to a recent New York Times article, humans have been at war with each other during at least 92% of all recorded history. And there has been no era of human history completely free from murder, rape, slavery, oppression, racism and other evils. Modern culture, of course, is no exception; the horrific mass shootings in the US, the perennial violence in the Middle East, African warlords starving and killing millions, the global epidemic of sex trafficking, and sadly the list goes on. I think we can all agree this is not how we ought to be treating one another.

Why do we see all this evil and suffering in the world? What’s wrong with mankind? How do we solve this problem? These questions are all closely related. And like anything else in life, we cannot find the solution to a problem until we understand the nature of the problem. The answer, in this case, goes back to origins where we find two major competing views. One is a problematic position that many of us hold, often unwittingly and inconsistently. The other position makes good logical sense of all the evidence but is often rejected without critical thought.

Position One: Natural Causes

The prevailing school of thought in the modern Western world seems to be that humans are essentially an evolved species of animal. We came out of the primordial soup at some point back in the mists of history, and over millions of years, we’ve evolved into what we recognize today as homo sapien. In other words, human beings are the product of the random, unguided process of evolution.

There is a wide range of variations within this view, of course, but they all fall under the general category of naturalism; the belief that everything arises from natural properties and causes (as opposed to supernatural or spiritual causes). This is the obvious position held by atheists and others who do not believe there is a god. But it’s also the de facto position of those who simply do not believe the universe was created by God and those who consider themselves “nones”. Those who hold to naturalism tend to overlook two important logical entailments that result from this worldview, both of which directly impact the issue of man’s cruelty to man.

First, naturalism necessarily maintains that morality arose out of nature; that our sense of “right” and “wrong” is a behavioral characteristic that evolved over time in order to foster a more successful propagation of the human species by helping human relationships (and, therefore, societies) operate more smoothly. For that reason, naturalists believe there is no objective standard of morality. Instead, morality is a relative concept that is defined differently within different cultures or societies.

Secondly, naturalism has an impact on the concept of man’s free will. If one believes the natural world is all that exists, the inescapable conclusion is that the human brain is merely a physical organ and there is no such thing as a “mind”. (see: The classic mind vs. brain debate that predates Aristotle.) So, rather than being abstract or immaterial objects, our thoughts are merely physical phenomena that occur within the brain. Stephen Cave explains:

Secondly, naturalism has an impact on the concept of man’s free will. If one believes the natural world is all that exists, the inescapable conclusion is that the human brain is merely a physical organ and there is no such thing as a “mind”. (see: The classic mind vs. brain debate that predates Aristotle.) So, rather than being abstract or immaterial objects, our thoughts are merely physical phenomena that occur within the brain. Stephen Cave explains:

The contemporary scientific image of human behavior is one of neurons firing, causing other neurons to fire, causing our thoughts and deeds, in an unbroken chain that stretches back to our birth and beyond… If we could understand any individual’s brain architecture and chemistry well enough, we could, in theory, predict that individual’s response to any given stimulus with 100 percent accuracy.

In other words, in a naturalistic view of the universe, mankind does not have free will. We are merely agents whose behavior is driven by the clockwork laws of cause and effect.

Taken together these two logical entailments generate some pretty serious questions. If one’s worldview does not recognize the objective categories of good and evil, on what basis can one condemn anyone’s actions as truly “evil”? Rather than calling them “wrong”, mass shootings would more correctly be described as culturally non-preferable. And if there is no such thing as human free will, how can anyone be held accountable for their actions? The logical outworkings of the naturalist view, then, require the ultimate conclusion that there is nothing wrong with human beings at all. Man’s cruelty to man is not a problem to be fixed, it’s simply a brute fact of nature. Since human beings are purely a biological byproduct of an indifferent universe, we are just as nature intended us to be. Therefore, mankind’s tendency toward violence, greed, and hatred should be accepted as entirely natural, and concepts such as morality, justice, and human dignity should be recognized as mere social constructs.

Of course, that is not how most people who hold a naturalistic worldview actually feel. In real life, they are just as horrified as the rest of us at senseless acts of violence, just as condemning of the people who perpetrate evil, and they cry out for justice as loud as the next guy. And they are right in doing so because any sane person recognizes that this is not how humans ought to treat one another. And here we find one of naturalism’s biggest problems; it is logically incoherent to simultaneously hold that naturalism is true and that man’s cruelty to man is objectively wrong. These are mutually exclusive concepts and both cannot be true at the same time. The two simple facts that (1.) humans all agree there are ways we ought to treat one another (whatever those ways might be), and (2.) humans regularly fall short of what they ought to do, represent an insurmountable problem for naturalism.

So how, then, do we solve the problem of evil within a naturalistic framework? In short, we don’t. (Or as they say in Maine, “You can’t get there from here.”) Within a naturalistic worldview, we simply find ourselves living in a violent and indifferent universe with no warrant to expect anything to change. It is what it is.

Position Two: Nature Plus

Over against the naturalist view is a view we might call Nature Plus. This view asserts that there is more to reality than merely the natural forces at work in the physical universe. This is the Christian worldview, and in it we see a completely different picture of who man is and where he came from and therefore, we find a completely different explanation of the problem of evil. This position not only makes sense of what we observe in the real world, it also provides us with hope and a solution.

Over against the naturalist view is a view we might call Nature Plus. This view asserts that there is more to reality than merely the natural forces at work in the physical universe. This is the Christian worldview, and in it we see a completely different picture of who man is and where he came from and therefore, we find a completely different explanation of the problem of evil. This position not only makes sense of what we observe in the real world, it also provides us with hope and a solution.

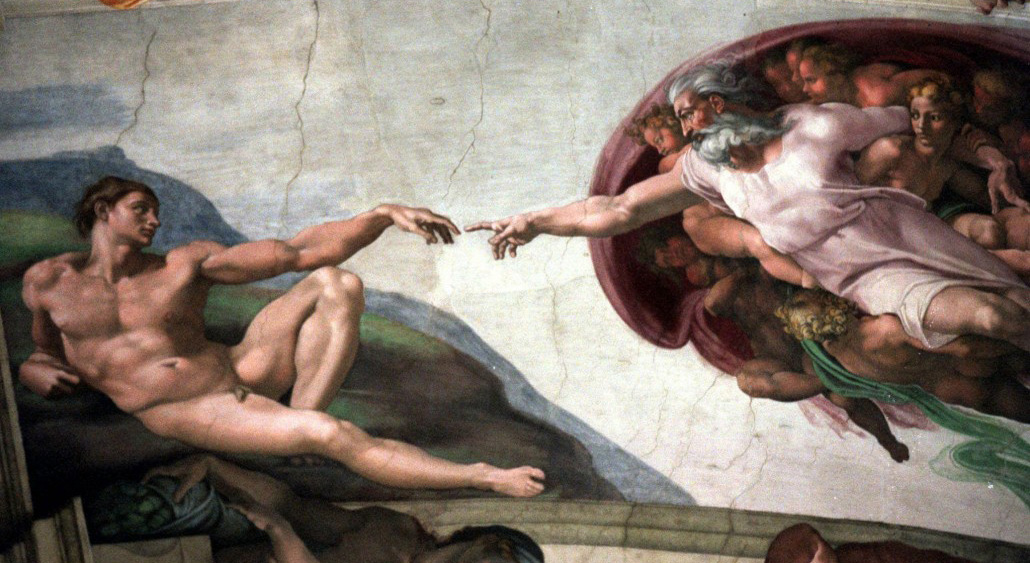

Christianity teaches that the universe was created by a loving Creator God. In this worldview, every human being has inherent dignity and value because, rather than being a biological byproduct of an indifferent universe, human beings were created by God in His image (imago Dei). Human life is sacred. This is why murder, racism, rape, slavery and all the rest can be denounced as objectively morally wrong with no hint of the logical inconsistency that plagues naturalism. In the Christian worldview, it’s never okay to treat another human cruelly. Why? Because he or she was made in God’s image and is loved by Him.

Additionally, where naturalism says humans are just as nature intended us to be, Christianity teaches the exact opposite; humans are not as we were intended to be. Instead, the vein of evil and cruelty we see running through human history is an abnormality that stems from the fact that something has been broken in the human race. We believe this happened at a specific time in history, when the first man and woman chose to rebel against God and subsequently fell from grace, introducing moral brokenness and sin into the world (Romans 5:12-20). Thus, the reason all humans inherently feel they ought to treat one another in a certain way is because God originally made us good; He wove His moral law into the essential makeup of every human being (Rom 2:15). And the reason humans regularly come up short is because of the historical moral fall of mankind, which brought with it brokenness and sin.

All of human history underscores the fact that no law, no philosophy, and no scientific discovery will ever solve the problem of man’s inhumanity to man. This is because the problem of evil is not a legal, philosophical, or biological problem. It’s a moral problem. And there is no other worldview that comes close to explaining the moral state of the world (not to mention the state of the human heart) with the accuracy that Jesus does. No other belief system offers the hope that is found in Him, either. Mankind was originally created good; our “normal” state was peace, goodness, and fellowship with God. But we fell from grace and we’re now living in an abnormal state of brokenness and rebellion. But God has not left us there! Instead, He came into the world Himself to provide for us a way to be restored to our normal state (John 3:16-18).

All of human history underscores the fact that no law, no philosophy, and no scientific discovery will ever solve the problem of man’s inhumanity to man. This is because the problem of evil is not a legal, philosophical, or biological problem. It’s a moral problem. And there is no other worldview that comes close to explaining the moral state of the world (not to mention the state of the human heart) with the accuracy that Jesus does. No other belief system offers the hope that is found in Him, either. Mankind was originally created good; our “normal” state was peace, goodness, and fellowship with God. But we fell from grace and we’re now living in an abnormal state of brokenness and rebellion. But God has not left us there! Instead, He came into the world Himself to provide for us a way to be restored to our normal state (John 3:16-18).

The bottom line is that mankind is broken and the only thing that can fix us is Jesus. He alone can transform human beings morally, from the inside out. And until that takes place there will be no real peace, no absence of violence, theft, hatred, lust, racism, and all of the ugly things that we see and do. Ultimately we need the transformation of the gospel in order to fix the problem of evil.

More than 100 years ago theologian and author G. K. Chesterton summed up this entire problem in just two words. In the early 1900’s the Times of London sent out an inquiry to famous authors, asking the question, “What’s wrong with the world today?” He responded simply:

“Dear Sir,

I am.

Yours, G.K. Chesterton”