Sovereign God, Free Man

If God is sovereign over all things how can mankind be genuinely free and held responsible for our actions?

The idea of a Creator God who is sovereign over all things is not a problematic concept on its own. The notion of a Supreme Being who controls nature, history and the universe is a thread that runs through many religions and faith traditions. This belief is at the core of the Judeo-Christian worldview as well, appearing as a consistent message throughout Scripture. Psalm 135:6 tells us, “The Lord does whatever pleases Him, in the heavens and on the earth, in the seas and all their depths.” This idea of God’s sovereignty echoes throughout the Old Testament (2 Chr 20:6, Job 42:2, Ps 115:3, Isa 46:10, Dan 4:35). And in the New Testament we not only see this idea underscored (Acts 7:48-50, Rom 9:19-21, Eph 1:11, 1 Tim 6:15), we also see that God has given His sovereign authority to His son, Jesus (Matt 28:18, John 3:35, John 17:2).

Likewise, the basic idea that man1 has free will and can therefore justly be held responsible for his actions is widely accepted. This concept is held to be true even among those who may publicly declare otherwise. Even moral relativists and atheistic thinkers (who hold to determinism via naturalism and, on that basis, deny man’s free agency) would want to seek justice if they were physically assaulted or had their property stolen. Indeed, the concept of justice—the idea that man should be held accountable for his wrong actions—is universal and finds plenteous scriptural support as well. One needs to look no further than the Decalogue (Ex 20:1-17) or the two greatest commandments as taught by Jesus (Matt 22:37-40) to understand that Scripture assumes man has the freedom to make moral choices.

Where major problems begin to arise is in trying to reconcile both of the truths outlined above; asserting that God is sovereign over all things including man and at the same time man is genuinely free and responsible for his choices. This is sometimes referred to as the Problem of Free Will and A.W. Tozer frames its inherent tension nicely:

If God rules His universe by His sovereign decrees, how is it possible for man to exercise free choice? And if he cannot exercise freedom of choice, how can he be held responsible for his conduct? Is he not a mere puppet whose actions are determined by a behind-the-scenes God who pulls the strings as it pleases Him? The attempt to answer these questions has divided the Christian church neatly into two camps, which have borne the names of two distinguished theologians, Jacobus Arminius and John Calvin. Most Christians are content to get into one camp or the other and deny either sovereignty to God or free will to man.2

Do the two concepts of God’s sovereignty and man’s freedom truly present a contradiction? Or are they simply a paradox? Or perhaps something else? To address this tension one needs to grapple with a wide range of topics including God’s omnipotence and omniscience, His providence, His relationship to time, man’s will, the nature of freedom and agency, and so on. This has led to a number of models and theories throughout the history of Christian thought that attempt to solve the Problem of Free Will. I want to take a brief survey of three positions held on this issue; the two major positions of Calvinism and Arminianism3, and a newer theory called Open Theism. Ultimately the position I will support is a version of Calvinism that is built on a more nuanced definition of compatibilist freedom in which I will argue that God’s sovereignty is exercised in both the motivation for man’s free decisions and the outworking of those decisions in the world. I will argue from the orthodox biblical teachings on God’s sovereignty, man’s freedom, and man’s moral culpability, and tie them together using both logical and philosophical lines of reasoning.

The Arminian View

At the heart of the tension, we are trying to resolve is the search for an understanding of agency that sufficiently explains how man can justly be held responsible for his actions. The starting point for this search is typically the nature of free will. The Arminian view is built on a libertarian understanding of free will which holds that man’s choices are not caused by anything outside of himself and any time he makes a choice he could have chosen otherwise. In other words, man is the ultimate originator of his own action and, in that sense, is sovereign over his choices.4

At the same time, Arminians maintain that God is sovereign and He has a divine plan that covers all things. Thus, in order to allow for a libertarian freedom in which man chooses his own path Arminians hold that God made a deliberate decision to limit His control over the universe. But since God in His wisdom made this choice freely it does not limit His sovereignty in any way. Further, this self-imposed limitation does not mean that God is powerless to guarantee His plans are carried out. In the same way that He sovereignly chose to create the world he sovereignly chose to give us, His beloved creatures, significant input into exactly how things will turn out.

But this brings up an important question. How can God guarantee His goals are achieved if He is not controlling every event and decision? This is where Arminians appeal to divine foreknowledge, claiming God has full awareness of man’s freely performed actions before they occur. And because God knows the future comprehensively, He is able to determine in advance how He will respond to our free actions to ultimately bring His plans to pass. Though God does not predetermine what free creatures will do, He can foreknow their actions and therefore choose to create a world containing those creatures and actions that serve His purposes. In addition to working through man’s free choices, God’s sovereign plan also includes His unilateral actions. He can and does work directly in the world through divine actions such as prevenient grace and miracles.

The Open Theist View

Open Theists subscribe to the same general sovereignty model as Arminians, and to the same libertarian view of man’s freedom. However, they adopt a more liberal, extra-biblical position on these issues. Open Theism affirms that God desires that each of us freely enter into a loving, personal relationship with Him through His Son, Jesus. And for that reason, God has made His plans for the future conditional upon our actions. Though Open Theists maintain the understanding of God as omniscient, they do not subscribe to the classical understanding of divine foreknowledge held by Arminians, which grants Him knowledge of what man will freely do in the future.5 Rather God invites man to freely collaborate with Him in ruling His creation and determining the course of history.6

Consequently, Open Theists believe that God has ultimately taken a risk in creating the world. Although in His omniscience God knows all the conceivable ways history may unfold, He cannot know what will actually happen because at least some part of the future is contingent on the free decisions of His creatures. Most Open Theists will acknowledge that their view is somewhat in conflict with orthodox Christian teachings, though they assert it is not as inharmonious as might be thought. Open Theists believe there is a need to rethink the emphasis on God as a perfect being who does not change in any respect because, in their opinion, this idea is not clearly taught in Scripture nor is it compatible with the nature of a loving God.7

The Calvinist View

Over against Arminianism and Open Theism, we find the Calvinist view, which is built on a fundamentally different understanding of man’s freedom. Rather than libertarian freedom, which says that any time man makes a choice he could have chosen otherwise, Calvinists hold to a compatibilist understanding of freedom. The central idea behind compatibilism is that, if determinism is true, every human action is causally necessitated by events prior to that action. Calvinists further assert that determinism is true, and freedom, when properly understood, is compatible with determinism.8

This view of freedom comes from Jonathan Edward’s concept of free will, which says that the human will is always determined by the strongest motive at the time the choice is made.9 According to Edwards, “There is scarcely a plainer and more universal dictate of the sense and experience of mankind, than that, when men act voluntarily, and do what they please, then they do what suits them best, or what is most agreeable to them.”10 In other words, we are free to choose and we will always make our choice based on our highest motivation at the time. Yet, at the same time, we know that what God determines will always come to pass (Eph 1:11). So, given this sort of free will, how is that God can maintain His sovereignty over the universe? Compatibilism says that, although our choices are made voluntarily and grounded in our strongest personal desire at the time of the choice, the desires and circumstances that facilitate our choices are a product of divine determinism. We see an example of this in the crucifixion where men willfully and voluntarily participated in the killing of Jesus, an event that was part of God’s determined plan from eternity past (Acts 2:23). So, in the compatibilist view, God’s sovereignty is exercised in the determining of the desires on which men freely act. As Schopenhauer famously stated, “Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills.”11

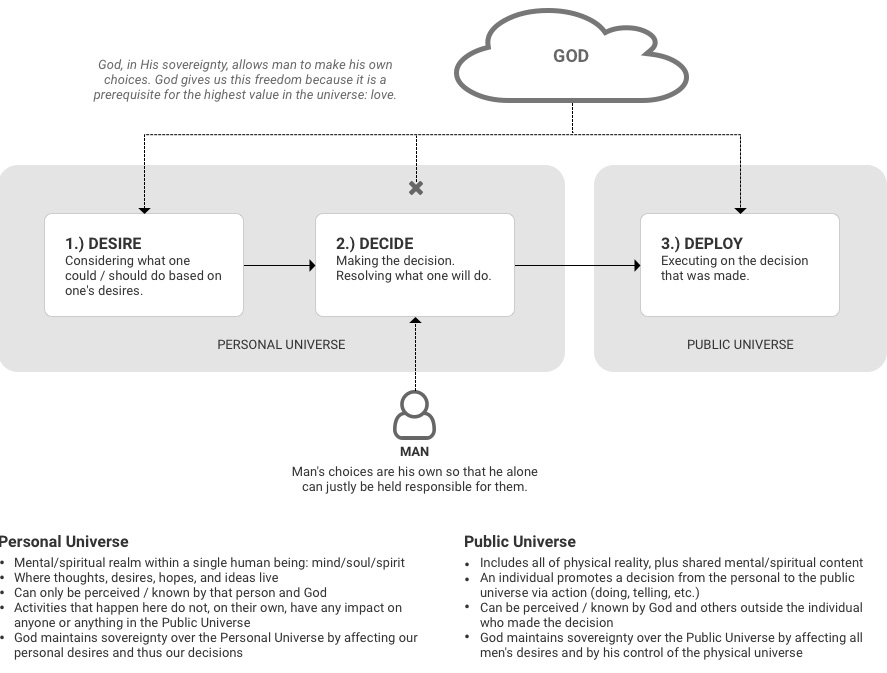

However, in a world where sin still clearly exists, the idea that God maintains His sovereignty by determining our desires introduces some problematic entailments regarding God’s relationship to sin. Does sin exist because God has determined we should desire it? Or because God is not always successful in influencing our desires against it? I believe God’s sovereignty can be more fully explained by drawing a distinction between the mental/volitional event of making a choice and the ultimate manifestation of that choice. These events are so intertwined we often consider them the same thing. But in reality, every decision is preceded by a mental process and succeeded by an action (Jas 1:14-15). God’s sovereignty may be exercised anywhere along this decision-action continuum, either before or after our choice is made (see Illustration 1 below). And it’s not until we take action that our decision graduates from the world inside us, what we could call our “private universe”, into the world around us, the “public universe”. It takes that outward action on our part to impact the world and ultimately challenge God’s sovereignty over the metanarrative of the universe. If our decisions remain private thoughts and we’re only firing off mental events that never manifest in the physical world, they do not directly impact the world. (Though our own salvation could be at stake, of course, if we were to waste our lives in sinful thinking.)

Illustration 1: The Decision-Action Continuum.

Left to our own devices men will always choose to sin and that choice is ours alone (Eph 2:1-3, Rom 7:15-20). God may choose to turn us over to our sin and allow us to freely make our sinful choices (Ps 81:12, Rom 1:24). In those instances, His sovereignty is maintained by controlling the outworking of our sinful choices after they have been made, so that God, and not our sin, is sovereign over the moral direction of the universe (Gen 50:20, Prov 16:9, Matt 10:29). On the other hand, prior to our decision, God may choose to work in our desires and circumstances so that what is most agreeable to us at the time of choosing leads us to choose rightly (Phil 2:13). In either case, man is a genuinely free moral agent who can justly be held accountable for his choices (Romans 2:6) and at the same time, God is completely sovereign over the universe; from the rise and fall of nations (Isa 40) to the inner workings of our relationships (Gen 20:6). In this way, God is entirely in control of all the events in the universe without taking away man’s freedom and, while He could perhaps be said to allow evil, He is not the author or source of evil.

Objection #1: Limiting Man’s Meaningful Freedom

This position naturally raises questions about how man can truly be free in such a universe. If God has planned and governs all things how can there be any meaningful human freedom? Calvinists believe that God directs and works through the distinctive properties of each created thing so that these things themselves bring about the results that we actually see in the world.12 In man, the properties He uses include our desires and motivations, which are what determine our will.13 As theologian John Feinberg puts it, “If the act is according to the agent’s desires, then even though the act is causally determined, it is free and the agent is morally responsible.”14 In other words, even though human actions are causally determined they are still free because at the time we are making our decisions we are aware of no restraints on our will from God.15 Thus the Calvinist view is able to hold together the two concepts of God’s sovereignty and man’s freedom without doing damage to either.

Objection #2: Limiting God’s Sovereignty

It might be argued that God’s sovereignty is limited by allowing man the freedom to make his own choices. But God’s ultimate authority in any area does not necessitate a specific outcome, it only means that God is the One Who ultimately decides what the outcome will be. Nothing can happen without His knowledge and consent. So it does not limit God’s sovereignty to say that, as the ultimate authority over man’s free will, God has freely chosen to allow man to make his own decisions. Especially since the reason He gives us that freedom is because, as stated in the Divine Gift-love Theodicy, “Love is the highest moral value and must exist in any world God creates. In any world where love exists, free will must exist.”16

1For brevity, I will use the shorthand term “man” to refer to all of humankind, homo sapiens, male and female alike. When doing so I will use male pronouns for grammatical consistency.

2A. W. Tozer, The Knowledge of the Holy (Bletchley, UK: Authentic Media, 2008), 144.

3The full range and depth of views held regarding God’s sovereignty and man’s free will are well beyond the scope of this paper. Thus, I am using the terms “Calvinism” and “Arminianism” to broadly describe two general schools of thought on the issue.

4J. P. Moreland and William Lane Craig, Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2003), 240.

5Gregory A. Boyd, God of the Possible: A Biblical Introduction to the Open View of God, (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2000), 11.

6David Basinger, The Case for Freewill Theism: A Philosophical Assessment (Downer’s Grove,IL: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 121.

7James Rissler, Open Theism, Published on The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Last accessed May 1, 2018 online at https://www.iep.utm.edu/o-theism/

8Moreland and Craig, Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview, 269.

9Jonathan Edwards, Freedom of the Will (Overland Park, KS: Digireads.com Publishing, 2013), 8. Kindle.

10Ibid., 8.

11Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Freedom of the Will: The Philosophy of American History (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1966), 531.

12Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994), 319.

13Jonathan Edwards, Freedom of the Will (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1754/2012), 5.

14John Feinberg, “God Ordains All Things” in Predestination and Free Will: Four Views of Divine Sovereignty And Human Freedom, ed. by David Basinger and Randall Basinger, (Downer’s Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1986), 37.

15Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine, 331.

16Robert Solberg, 2018, “If God Is All-good, All-powerful and all-Wise, Why Is There Evil In The World He Created?” Position paper, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 9.

Anonymous

Calvinism is so obviously from Satan himself.

Anne, Toronto

Barry Jones

An atheist is first warned by an Arminian to stay away from the “heretical” Calvinist gospel because it makes God the author of sin, a teaching so inexcusably blasphemous that none of its advocates are biblically qualified to be evangelists in the first place. It makes no sense for the atheist to start out his Christian walk thinking a blasphemous doctrine constitutes spiritual truth.

Then the atheist is warned by a Calvinist to stay away from the “heretical” Arminian gospel, because a doctrine of libertarian freewill makes the sinner become his own god, a teaching so inexcusably blasphemous for supporting self-idolatry that none of its advocates are biblically qualified to be evangelists in the first place. It makes no sense for the atheist to start out his Christian walk thinking a blasphemous doctrine constitutes spiritual truth.

Thus, the atheist has very strong justification, from the collective advice of a majority of Trinitarian Christians, to conclude that both interpretive options constitute inexcusable heresy, and to ultimately conclude that yes, the reason the bible seems to support both Calvinism and Arminianism is because it actually does, i.e., the bible contradicts itself, i.e., the doctrine of full biblical inerrancy is false.

This is a great shame to inerarntists who take sides in the Calvinist/Arminian controversy, because the inerrancy doctrine (i.e., inerrancy is limited to the originals) isn’t even a biblical teaching in the first place. One wonders how much more unity there would be in Christianity if all Christians recognized the inerrancy doctrine for the sinful bit of word-wrangling strife it has always proven itself to be. Christians who denied bible inerrancy would probably have adopted softer approaches to doctrine that would have facilitated respect for contrary interpretive opinions and thus facilitated more unity in the body of Christ.