Is the Law of Moses Eternal?

When God entered into a covenant with Israel at Mount Sinai, was that covenant expected to be eternal? The Law of Moses served as the terms of that covenant. If Israel kept the 613 mitzvot (commandments) of the Law of Moses, the nation would be blessed. If not, the covenant would be broken and Israel would be cursed (See: Deut 28-29). So was the Law of Moses intended to remain binding and unchanged forever? According to both Judaism and the modern movement called Torahism, the answer is a resounding yes! But is that what the Bible really teaches? Let’s take a look.

Eternality

First, let’s consider the concept of eternality. The dictionary defines eternal as “without beginning or end; lasting forever; always existing (opposed to temporal).” So as our point of reference for eternality, we can look to God. Christianity, Judaism, and Torahism all agree that He is eternal,1 without beginning or end:

Before the mountains were born

—Psalm 90:22

or you brought forth the whole world,

from everlasting to everlasting, you are God.

By definition, this tells us that the Sinai Covenant, although it was given by an eternal God, is not eternal. Why? Because, unlike God, it had a beginning. Noted Jewish Rabbi Adin Even-Israel teaches that the covenant was not given to mankind until Mount Sinai, and the apostle Paul agrees (Rom 5:13-14).

God created the universe and humanity, including a host of Old Testament saints—Adam, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Job, Joseph, etc.—who all lived and died before He gave Israel the Law of Moses. The world saw the Fall and the Flood and the tower of Babel before the Law existed. The Jews spent centuries in slavery in Egypt before the Law of Moses was born. Clearly, the Law of Moses is not eternal. It was given at a specific time in history (~1400 B.C.) through a particular man (Moses).

How About Everlasting?

Okay, so maybe the Law of Moses is not technically eternal because it had a beginning. But once given, was it intended to remain binding and unchanged forever? Our Jewish and Torahist friends say yes and cite several passages to support that claim:

- “Your word, Lord, is eternal; it stands firm in the heavens.” (Psalm 119:89)

- “Yet you are near, Lord, and all your commands are true. Long ago I learned from your statutes that you established them to last forever.” (Psalm 119:151-2)

- “All your words are true; all your righteous laws are eternal.” (Psalm 119:160)

- “Know therefore that the Lord your God is God; he is the faithful God, keeping his covenant of love to a thousand generations of those who love him and keep his commandments.” (Deuteronomy 7:9)

- “These are the decrees and laws you must be careful to follow in the land that the Lord, the God of your ancestors, has given you to possess—as long as you live in the land.” (Deuteronomy 12:1)

- “He remembers his covenant forever, the promise he made, for a thousand generations.” (1 Chronicles 16:15)

The emphasis in the verses above is mine. I added it to underscore that there seems to be a very strong case for the everlasting nature of the Law of Moses. But are the original Hebrew phrases behind the verses above intended to literally mean “without end, to be continued infinitely?” This is where things get interesting.

What’s In a Word?

To understand what the Bible means by everlasting, we need to remember that almost all of the Old Testament was written in biblical Hebrew,3 which is an archaic form of the Hebrew language. When translating any text, there is not an exact one-to-one correlation between languages. This is especially true when translating biblical Hebrew—which has less than 9,000 words—into modern English, which has more than 200,000 words!

Our goal should be first to interpret any passage of Scripture within the context of the book in which it was written, and then within the context of the entire Bible. In most cases, the English translations give us what we need. But when it comes to examining the claims of Judaism or Torahism, it is sometimes necessary for us to parse the English translations a bit more carefully. For example, consider the following verse:

So the sons of Israel shall observe the sabbath, to celebrate the sabbath throughout their generations as a perpetual covenant.

—Exodus 31:16, NASB

In this verse, the Hebrew word עוֹלָם (`olam) is translated as the English word perpetual. In English, this word means “continuing forever; everlasting, valid for all time.”4 In ancient Hebrew, however, the word olam is not so cut-and-dry. It has a much broader definition. According to The NAS Old Testament Hebrew Lexicon, that single word can mean:

- long duration, antiquity, futurity, forever, ever, everlasting, evermore, perpetual, old, ancient, world

- ancient time, long time (of past)

- (of future) forever, always

- continuous existence, perpetual, everlasting

- indefinite or unending future, eternity

This wide range of possible meaning explains why, in the New American Standard Bible translation, the Hebrew word olam is rendered 435 times as 25 different English words or phrases:5

| ages | ever | long time |

| all successive | everlasting | never |

| always | forever | old |

| ancient | forever and ever | permanent |

| ancient times | forevermore | permanently |

| continual | lasting | perpetual |

| days of old | long | perpetually |

| eternal | long ago | |

| eternity | long past |

This range of meaning raises an important question. In the verse quoted from Exodus above, how do we know if the phrase perpetual covenant was intended to mean a covenant that is valid “for all time” or “for a long, indefinite duration” or something else? When it comes to Scripture—especially the writings in biblical Hebrew—a word’s intended meaning must be drawn from the context of its use. We need to view it in light of the larger body of teaching in the passage, the book, from that author, and ultimately from the entire Bible.

The passage we’re looking at says, “So the sons of Israel shall observe the sabbath, to celebrate the sabbath throughout their generations as a perpetual covenant” (Ex 31:16, NASB). In Judaism, the context for determining the meaning of this verse is limited to the Old Testament. Christians and Torahists, on the other hand, accept the New Testament as the Word of God, so they have a larger context to consider. They must determine the meaning of the word within the context of both the Old and New Testaments. This makes a big difference. God has sovereignly chosen to reveal His will to mankind over time, rather than all at once. So when new information is introduced along the biblical timeline, we have to interpret the former Scriptures in light of the latter. They are both the inspired Word of God, of course. But often the newer information helps to explain or illuminate the older.

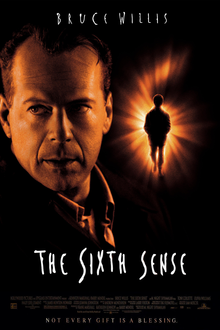

It’s like the movie The Sixth Sense. Near the end of the film, we get the shocking revelation that the psychiatrist Malcolm has been dead the whole time. If we were to go back and re-watch the movie, we would discover that the revelation at the end does not change the content or meaning of the earlier scenes. In a sense, it makes them even more true. We would notice the clues the filmmaker added, which were sitting in plain sight the whole time. We would realize that Malcolm’s wife wasn’t just ignoring him or being cold, she was acting like he didn’t exist because he was dead and she couldn’t see him. And we would notice that Malcolm never touches or moves objects in front of anyone other than the young boy, Cole, who can see dead people. And that Malcolm never directly interacts with the boy’s mother. These clues were there for us all along, but it’s not until we receive the revelation later in the film that we fully understand what they mean.

The same thing is true of the Bible. Once we become aware of the new revelations that God gave us through Yeshua and the authors of the New Testament, it puts the Tanakh (aka Hebrew Bible or Old Testament) into sharper focus. In a sense, it makes the Hebrew scriptures even more true. Now when we go back and re-read the Old Testament, we discover clues the Author added which were sitting in plain sight the whole time. The Old Testament wasn’t wrong, and it’s certainly not to be thrown away. Because of future revelations from God, however, it means something more than we thought. And by understanding the Hebrew Bible more fully, it becomes even more real and amazing.

Looking at the text in Exodus 31:16, we can see why, at the time it was given, the early Jews concluded the phrase “a perpetual covenant” meant that the covenant would last literally until the end of time. At that time, Israel had no idea there was going to be a New Covenant. That wouldn’t be revealed until the prophet Jeremiah. The Jewish authors of the New Testament, on the other hand, had the benefit of reading that passage in light of the new information later revealed by Yeshua. They realized that God’s promised New Covenant (Jer 31:31-34) was inaugurated in the first century through Christ’s death on the cross (Matt 26:28; Luke 22:20; 1 Cor 11:25). And further, they recognized that the Sinai Covenant—which was described as ovlam berit (a perpetual covenant) in the Torah—had been become obsolete and outdated at Christ’s resurrection (Heb 8:13). In light of this newer information, we are forced to conclude that the Hebrew phrase ovlam berit (perpetual covenant) in Exodus 31:16 could not have meant “until the end of time.” If that was the case, Scripture would be contradicting itself. It must have instead meant something like a long, indefinite duration.

The Everlasting Priesthood

We find this same thing with the establishment of the “permanent” or “everlasting” Levitical priesthood in Exodus 40:15. This is translated in the King James Version as, “…an everlasting priesthood throughout their generations.” Here, the Hebrew word `olam is translated into the English word everlasting. And if the word everlasting in this passage literally meant “forever,” then the priesthood prescribed by the Law of Moses—which was strictly limited to descendants of the tribe of Levi5—would be the only priesthood until the end of time. However, in the New Testament, we find that Yeshua, Who descended from the tribe of Judah, not Levi, is now our High Priest (Heb 7:14-18). And what’s more, all Christians, whether Jew or Gentile, are now a royal priesthood through the indwelling of the Holy Spirit (1 Peter 2:4-10). So when the Law of Moses described the Levitical priesthood as “everlasting,” it could not have meant it would literally last until the end of time. Instead, it must have meant that the priesthood was to last for something like a long, indefinite duration.6

There are numerous examples like this throughout Scripture where English words and phrases like forever, eternally, throughout your generations, unto a thousand generations, and as long as you’re living on the earth could not actually mean “until the end of time.”7 However, here’s where it gets tricky: there are also many passages where that’s exactly what those words mean. For example, God and His attributes are eternal,8 His Word will endure forever,9 and His love is literally unending.10

This is why context is so important. We need to be careful in our interpretation of any given verse or passage. When earlier verses seem to imply something will last forever and later verses indicate that thing has ended, it should give us pause. To accurately reconcile seemingly contradictory passages, we need to view what we’re reading in light of the entire Bible. This is why I mentioned that the early Jews were operating within a smaller Scriptural context. It was not a wrong context, just incomplete.

Our Torahist friends find themselves in the untenable position of accepting the new information found in the New Testament, yet restricting the interpretation of that information to the context of the Hebrew Bible. In the end, the interpretation of the Law of Moses as eternal and everlasting does not align with Scripture as a whole. And this is where we bump into the thorny issue of terminology. Is God’s Word eternal? Yes. Is His perfect law eternal? Of course! Are His promises eternal? Absolutely. But as I unpack further in my book Torahism: Are Christians Required to keep the Law of Moses?, the Mosaic Law was never intended to last forever.

[1] Genesis 1:1; Psalm 90:2; John 1:1; Romans 1:20; 1 Timothy 1:17.

[2] Also see Deuteronomy 33:27; Isaiah 26:4; Jeremiah 10:10.

[3] According to the International Bible Society, a few chapters of Ezra and Daniel and one verse in Jeremiah were written in biblical Aramaic, rather than Hebrew.

[4] Merriam-Webster’s definition of “perpetual.”

[5] See Exodus 40:15 and Deuteronomy 18:5. The fact that the Levitical priesthood has now ended is one of many clues that tell us the Law of Moses is no longer active and binding. This issue is discussed in greater detail in my book Torahism: Are Christians Required to keep the Law of Moses? See chapter 12: The Temple: Priests, Sacrifices & Worship.

[6] This is evident in the way the word ‘ovlam is rendered in other Bible translations. For example, in the NIV, the English word “everlasting” is not used in this verse at all. Instead, it refers to “a priesthood that will continue throughout their generations.”

[7] Exodus 21:6; 1 Kings 8:13; Jonah 2.

[8] Genesis 21:33; Deuteronomy 32:40; Isaiah 40:28; Psalm 100:5, 117:2.

[9] Isaiah 40:8; Psalm 33:11, 119:89.

[10] Isaiah 54:8-10; Jeremiah 31:3; Psalm 109:2.

hedgerowperspective

What a crock! God gave His instructions for living from the beginning. Cain and Abel knew the difference between appropriate and inappropriate sacrifices. Noah knew the difference between clean and unclean animals. He also knew that God requires sacrifice. Abraham is commended for righteous living and righteousness is defined by the Bible as keeping Torah. The Israelites were keeping Sabbath before Sinai. Moses said that heaven and earth both bear witness to the validity of Torah. Jesus proclaimed that Torah and the Prophets will be in undiminished effect for as long as heaven and earth remain. In spite of all claims to the contrary, Paul taught and practiced Torah to his last days. (Acts 28:23) Both Revelation 12:17 and 14:12 make it clear that God’s Family is made up of those who follow Jesus by obeying Torah.

Scripture makes it clear that God NEVER changes. He made many promises to Israel, and He WILL fulfill them. He did not “replace” Israel with some other entity. That would require Him to change. He has not and will not. He will reunite and redeem the House of Israel and the House of Judah. If He can break His promises to them, He cannot be trusted. Everything wrong with modern Christianity is attributable to the satanic practice of interpreting earlier scripture in light of latter. The beginning of any book gives information necessary for understanding what comes later. Anyone who attempts to understand the last fourth of the Bible without the instruction of the first three fourths will, as you have, just make stuff up.

R. L. Solberg

Amen, Hedgerow! God never changes. And He did not “replace” Israel with some other entity. I agree with you there, as well. Thanks for your comment. I also agree that God gave mankind His instructions regarding sacrifices in the beginning. We see sacrifice happening long before the Law of Moses was given. But then, with the giving of the Mosaic Law, we see those instructions change. God never changes, and neither do the universal principles of the Law of God. However, those principles are expressed in different ways at different times. Not because God changes, but because mankind does.

For example, God’s principle of blood sacrifice for sin actually began in the Garden when God made clothes for Adam and Eve out of animal skins (Gen 3:21). Later, just prior to the giving of the Mosaic Law, His unchanging principle of blood atonement becomes even more apparent. In the Lord’s commandment to Israel to sacrifice the Passover Lamb, we explicitly see the shedding of blood secure the salvation of God’s people (Ex 12:6-13). The Passover sacrifice made at the end of Israel’s time in slavery in Egypt marked the beginning of ritual sacrifice. Then, under the Mosaic Law, the specific expression of God’s unchanging principle of blood atonement evolved into temple sacrifices. God now required the regular shedding of the blood of bulls and goats to atone for the sins of the High Priest and of Israel (Lev 16). His unchanging “blood atonement” principle had come to be expressed as a repeated ceremony in the temple services of God’s people.

Centuries later, under the New Covenant, God’s law of blood atonement remains. It was not abolished and it did not come to an end. But the specific expression of His principle changed. Do Christians today still have a sacrifice? Yes, we do! Christ is our sacrifice. Under the New Covenant, “we have been sanctified through the offering of the body of Jesus Christ once for all” (Heb 10:10). The blood sacrifice required by God’s Law is now fulfilled in the eternally-binding sacrifice of Jesus “once for all.”

Shalom,

Rob

Anonymous

What you fail to realize is that the Laws of Moses were not Moses’ Laws but the Laws of Moses are directly from God. When you understand that God gave everything that Moses wrote, then, you will realize it is eternal.

You also fail to realize that the Laws of Moses are not LAWS. When you say LAWS, in our Westernized mindset, it is somewhat negative. The Laws of Moses are never negative but they are instructions, they are the way to live, they are directions, in other words, these are the cultural mindset of God that He was giving to Moses. God was telling Moses, this is who I am, this is what I love and this is what I think. When you realize that God was giving His own culture to Moses, then, that is eternal.

When you realized that every word that God says, it is eternal.

For example, what God created and He said, let there be, creation never stops, the land, the stars, the trees, the animals, and people are still being created and it will be eternally because God said let there be, His words are eternal.

When you humble yourself and really seek God, He will reveal Himself to you. But when you limit His words, when you reject His instructions, it is like you are rejecting God.

R. L. Solberg

Thanks for weighing in! I’m not sure what makes you think I don’t know that the Law of Moses was given by God. I refer to the commandments as the “Law of Moses” because that is the term that Scripture consistently uses to refer to the commands that Yahweh gave Israel at Mount Sinai through Moses (Josh 8:31-32, 23:6; Judges 4:11; 1 Kings 2:3; 2 Kings 23:35; 2 Chron 23:18, 30:16; Ezra 3:2, 7:6, Neh 8:1; Dan 9:13; Luke 2:22, 24:44; John 7:23; Acts 13:39, 15:5, 28:23; 1 Cor 9:9; Heb 10:28).

God’s Word is absolutely eternal! But not every command He gives is eternal. For example, once Adam was ejected from the Garden, God’s command not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil was no longer in effect. Same thing with Noah and the flood. Not just God’s commands to build the ark before the flood. But I also gods commands about food after the flood. In Genesis 9:1–3, God tells Noah he can eat literally anything. He said, “Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you. And as I gave you the green plants, I give you everything” (Gen 9:3). But then, centuries later, God gave Israel new instructions about what food could and couldn’t be eaten (Lev 11). Same thing with God’s command to Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. We are not all commanded to sacrifice our sons. That command was for Abraham alone. So God’s commands are not all given to all people for all times. And this is true of the Law of Moses; it was a specific set of commands given to a specific group of people for a specific length of time (Gal 3:24-25).

That said, there are, of course, many of God’s commands which are universal; namely the commands having to do with morality (right and wrong). Those never change! So we have to approach God’s commands with some level of nuance. It’s just not biblical to claim that everything God has ever commanded is required of all people at all times forever.

Blessings, Rob

Kenneth Brownsher

Jeremiah and the New Covenant have Nothing to do with Jesus! “Thus says God, Who establishes the sun to light the day, the laws of the moon and stars to light the night, Who stirs up the sea into roaring waves, Whose name is the Lord of Hosts: ‘If these laws of nature would ever give way before Me,’ says God, ‘only then shall the offspring of Israel cease to be a nation before Me for all time.’ ” (Jeremiah 31:34-35)

“But fear not, O Jacob My servant, neither be dismayed, O Israel, because I shall redeem you from afar, and your children form the land of their captivity; and Jacob will again be quiet and at ease and none shall make him afraid. Fear not, O Jacob My servant, says God, for I am with you. For I will topple all the nations to which I have driven you. But of you I will not make a full end. I will correct you in just measure, but I will not utterly destroy you.” (Jeremiah 46:27-28)

Eli

Hashem, the sole Creator of everything in the universe, is with You Kenneth Brownsher…which Solberg knows full well having to work so hard day and night trying to come with ways to defend the indefensible – complete falsehoods which most people are coming to realize for what they are… and hopefully very soon, Hashem-willing perhaps as some of you are reading this, will all.

Garrett Speck

In reading the comments, I understand the difficulty. Etymology can seem like a way to “dismiss” what we don’t like. But when translating a language, there is rarely a “wooden” one to one correlation. Our english translators do an amazing job at getting as close as we can, but sometimes our language lacks the words to accurately portray the original language. Best example I can think of is the חֶ֥סֶד of God. We translate loving faithfulness or loving kindness, but it goes beyond that. I believe עוֹלָם falls into that same category of lacking the proper english word(s) to express it. I understood עוֹלָם to carry the sense of a period of time so far away, that Moses could not see the end of it. Thus it is a really long time; from Moses’ perspective, it was forever.

The law was/is good, but as you point out, it was only a guardian for a certain period of time. It pointed to humanities need for Jesus, since it lacked the power to justify or deal with our sin (Gal.2:16). It could only point our sin out. If someone thinks that they can follow the whole law perfectly, then I think they not grasping the severity of their own condition; of humanities condition. We need Jesus and not the law. And hopefully by his grace and the Spirit, we will live out the law in our love for one another.

On a related note, what are your thoughts on the law being “eternally upheld” in Jesus? I heard this interpretation and thought it was interesting. We are now “in Christ” and reckoned as righteous, because he gives us his righteousness. We are seen as perfectly following the law since we are in Christ. Jesus eternally upholds the law, therefore making it eternal. I suppose it would depend on ones understanding of fulfillment. Thanks for the post.

Anonymous

In my view, there is actually a large degree of agreement between the views of the author and those who commented. I think the biggest challenge to the church is to have a proper understanding of what a covenant is, as opposed to what a law is. The Mosaic law (stipulations of what to do and what not to do) is not the covenant, but the law is part of the terms and conditions of the Old Covenant between God and Israel. Accordingly, there would be a huge degree of overlapping between the Old Covenant and the New Covenant, as far as the stipulations about “right and wrong” are concerned. Murder, theft, idolatry, fornication, etc would of necessity be part of both covenants. But the Old (Mosaic) Covenant contains, in terms of ceremonial requirements, many shadows of the reality that came in Christ. Therefore those requirements would differ between the Old Covenant and the New Covenant. So when Jesus said in Matthew5 that He did not come to abolish Torah, but to fulfil or complete it, He made a statement that implied two things. On the one hand He did not abolish the Torah, but on the other hand He made it clear that there were aspects in the Torah that could not remain the same – those parts that He came to fulfil. People that claim that they observe the Torah can actually never make such a claim, because that cannot observe all its requirements, it is impossible to do. There is no temple. No animal sacrifices can make atonement for sins. It no longer makes sense to keep the feasts and appointed times of God with their “shadow” content. The way to celebrate them now is to celebrate their fulfilment in and by Christ, such as Passover, or the feasts focussing on His return. The content has changed – from the shadow to the reality in Christ. The same would apply to all the punishments in terms of the Old Covenant. Can anybody who claims to be Torah compliant then claim that they apply those punishments? Again, the New Testament makes it clear that Christ has redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us (Gal 3:13). Once again, He fulfilled the requirements and “completed” that aspect of the law in that manner. Gal 4 makes it clear that the two covenants are distinct covenants (depicted by Hagar and Sarah), but, there would of necessity be a huge degree of overlapping in content, especially as far as moral laws are concerned, as well as the numerous “shadow” requirements in the Old Covenant which were fulfilled by Jesus to give them their true meaning in the New Covenant.