The Easter Date Controversy

There is a fascinating history behind the modern controversy regarding the date on which Christians ought to celebrate Easter. And it’s not as black-and-white as you might think. Our examination begins in an upper room in Jerusalem near the end of Jesus’ ministry. (FYI: You can watch a video summary of this article here.)

The Last Supper

Jesus’ final meal before His crucifixion was a Passover meal taken with His Jewish disciples and friends. This was the “Last Supper,” as recorded in the Gospels (Matt 26:17–30; Mark 14:12–26; Luke 22:7–39; John 13:1–17:26) and mentioned by Paul (1 Cor 11:17-34). God’s appointed times are significant, and the importance of Jesus’ final meal being a Passover (Pesach) cannot be overlooked. The meaning was certainly not lost on the NT authors, who viewed Jesus as our Passover lamb (John 1:29, 36; 1 Cor 5:7; 1 Peter 1:19; Rev 5:6-8). Indeed, Luke began his narrative of the Last Supper with a bit of prescient foreshadowing: “Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the Passover lamb had to be sacrificed” (Luke 22:7). Thus, in Scripture, Jesus’ last supper is inexorably linked to the Jewish holiday of Passover. Indeed, the NT teaches us that the Passover feast itself is a shadow that prefigures Christ (Heb 10:1).

The connection between Passover and Christ is perhaps understood by messianic Jews better than anyone else. These are Jews who keep the feasts and have come to believe in Yeshua HaMashiach (Jesus the Messiah) as the One foretold in Hebrew Scripture. I have participated in a Passover seder with a messianic Jewish organization called Jews for Jesus and was amazed at the depth of connection between that ancient Torah feast and Jesus of Nazareth. But of course, our current interest is the date of Easter, so this isn’t the time or place to head down that captivating rabbit trail. Suffice to say, the connection between Passover and Christ is significant and Scriptural. (If you want to learn more, I recommend the books Christ in the Passover by Ceil & Moishe Rosen and The Passover King by Travis Snow.)

Celebrating the Resurrection in Antiquity

For the Jewish people, there was one sacred Spring season: Passover. And it was in the midst of that holy season that Yeshua, our Passover lamb, died for our sins and rose from the dead. In fact, His death coincided with the Passover sacrifice (Pesach), He was resurrected on the Day of Firstfruits (Yom Ha Bikkurim), and fifty days later, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit (Pentecost) happened at the Feast of Weeks (Shavuot). The connection between these critical NT events and the sacred days that God appointed in the Torah cannot be ignored. This is no coincidence!

Initially, the early believers (who were mostly Jewish with a few Gentiles sprinkled in) celebrated Messiah’s death and resurrection in the midst of Passover. In Paul’s first letter to the church at Corinth—some of whom were God-fearing Gentiles and heard the gospel in the synagogues, so they were familiar with the Jewish calendar and customs—he writes:

Cleanse out the old leaven that you may be a new lump, as you really are unleavened. For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed. Let us, therefore, celebrate the festival, not with the old leaven, the leaven of malice and evil, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth

1 Corinthians 5:7b-8

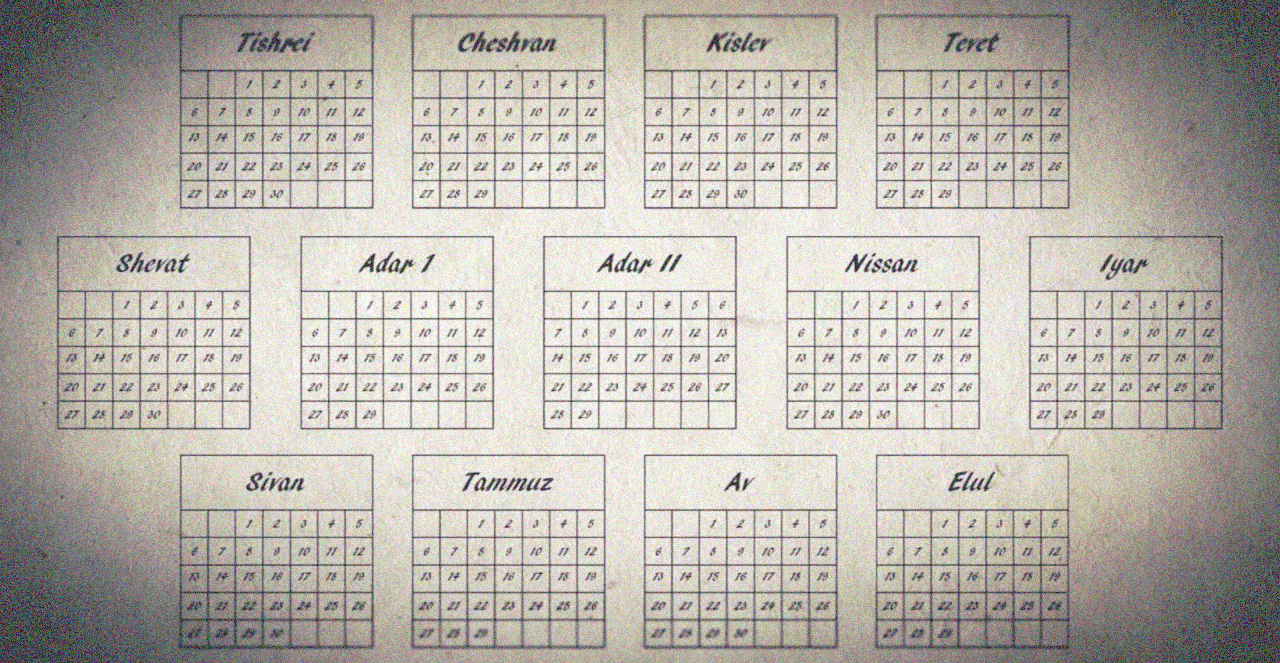

Thus, whether Paul meant it metaphorically or literally, it was during the Passover that Messiah’s death and resurrection were originally celebrated. Over the following decades, a tradition developed that ultimately divided the Eastern Church from the Western Church. One tradition followed the Jewish calendar and celebrated Yeshua’s death and resurrection beginning on the 14th day of the Jewish month of Nisan, in the midst of Passover. This was the actual date of Yeshua’s Last Supper. Gentile Christians, who felt no allegiance to a Jewish calendar, often preferred to commemorate the Resurrection on the first day of the week, since Sunday was the day when Jesus’ tomb was discovered empty. And they chose the first Sunday after Passover to celebrate the Resurrection.

The earliest mention of Christians celebrating the Resurrection comes to us from the second-century writings of Justin Martyr and Tertullian. And it’s clear that the observance had been occurring prior to their writings. Many historians believe the annual remembrance of the Resurrection among Christians dates back to the first-century. In fact, we find evidence in the NT that the commemoration of (or at least reflection on) the Resurrection may have occurred as often as weekly among the first Christians. In the NT we see believers had begun gathering on the first day of the week (John 20:19, 26; Acts 20:7; see also Rev 1:10) to “break bread,” a phrase commonly used in the NT to refer to the Lord’s Supper.

At that time, “the church” was a loose network of communities scattered across the eastern Roman empire and lacked a central authority. Each community, led by a local bishop,2 was free to choose how (or if) they wanted to commemorate the Resurrection. Thus, some early Christian communities would celebrate the Resurrection on 14 Nisan (those who did so were eventually referred to as Quartodecimans) while others chose the Sunday after Passover. Over the course of the first few centuries of the Christian faith, this disagreement on the proper date to annually commemorate the Resurrection became a significant controversy. Early Christian historian Eusebius of Caesarea (d. 339) wrote:

A question of no small importance arose at that time [the time of Pope Victor I c. 190]. The dioceses of all Asia, according to an ancient tradition, held that the fourteenth day, on which day the Jews were commanded to sacrifice the lamb, should always be observed as the feast of the life-giving pasch, contending that the fast ought to end on that day, whatever day of the week it might happen to be. However, it was not the custom of the churches in the rest of the world to end it at this point, as they observed the practice, which from Apostolic tradition has prevailed to the present time, of terminating the fast on no other day than on that of the Resurrection of our Saviour.

Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, V, xxiii

As the Christian Church matured and grew, it began encountering heresies that arose out of its diverse communities and teachers. Accordingly, maintaining unity and biblical fidelity across the rapidly-spreading faith communities became important. So finally, in AD 325 the first-ever ecumenical (“global”) meeting of Church leaders was held. More than 250 bishops from across the Roman empire gathered in the city of Nicaea (in modern-day Turkey). They were called together primarily to discuss the problematic Arian controversy, however, the official date for Easter was also debated during the council. By this time, Christianity had become a religion predominantly composed of Gentiles so celebrating the Resurrection on a Sunday (the Lord’s Day) every year was already the more popular option. Consequently, it was no surprise that the bishops at the council voted to officially do so.

Did the Church Go Too Far?

In the early years of the Church, the “new” religion of Christianity struggled to find its own identity. Early Christians had to wrestle with the staggering implications of the ministry and person of Christ. His work, His ministry, and His teachings were so paradigm-shattering they would ultimately take centuries to work out.3 So it’s fair to ask if the early church went too far in trying to separate itself from Judaism.

In the first century, Judaism was not a monolithic belief system. There were various sects—Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, etc.—that were often in sharp disagreement with one another over theological matters that were not insignificant. The Christian faith grew out of this Jewish culture and was initially seen as just another Jewish sect (often referred to as the “Nazarenes”). Yeshua was Jewish, as were His disciples and Apostles, and the NT authors.4 Moreover, Yeshua is clearly portrayed in the NT as the Jewish Mashiach (Messiah) who had been promised in the Hebrew Bible. Indeed, the title of “Christ,” which appears more than 500 times in the NT, means “Messiah.” If we were to read “Messiah” in place of “Christ” throughout the NT, the message becomes crystal clear. For example, “And he asked them, ‘But who do you say that I am?’ Peter answered him, ‘You are the Messiah.’” (Mark 8:29). Yeshua is portrayed in Scripture as fulfilling the Law and the Prophets (John 1:45), the continuation of the Story that began in the Hebrew Bible. Jesus Himself tells us this on several occasions (Luke 4:17-21, 24:25-27, 24:44,). Consequently, the identity of Yeshua was the primary cause of conflict between the early Christians and the Jews. Was He the Messiah or not? This conflict began as another sectarian dispute within the Jewish community, which we see reflected as early as the NT writings themselves.

Anti-Semitism?

It must be noted that, contrary to some modern claims, the early Christians were not animated by anti-Semitism. Indeed, to apply the modern concept of “racism” to ancient cultures is an anachronistic error. As Jewish scholar, Shaye J. D. Cohen points out,

Anti-Semitism did not exist in antiquity. This term was coined in 1879 by a German writer who wished to bestow “scientific” respectability on the hatred of Jews by arguing that Jews and Germans belong to different species of humanity (“races”). But the ancients did not have anything resembling a racial theory . . . They observed that different nations had different moral characteristics . . . But did not explain these differences by appeal to what we would call a racial theory. Instead, they argued that climate, soil, and water determine both the physical and moral characteristics of nations. Therefore, the notion of anti-Semitism is inappropriate to antiquity.

Shaye J. D. Cohen, From The Mishnah to the Maccabees (2014), p. 39

While anti-Semitism as a racial issue did not exist in antiquity, anti-Judaism certainly did. And, as noted above, the anti-Jewish sentiments we find in the writings of the early Church fathers were based on the person of Yeshua. The disagreements were theological in nature, centering on Judaism’s rejection of Jesus as the Messiah through Whom salvation had come. As such, the attitudes and actions of the early Christians do not reveal an attempt to separate from the Jewish Scriptures, nor even from extra-biblical rabbinic interpretations of the Tanakh;5 Christianity has always accepted the Hebrew Bible as inspired, authoritative Scripture. Rather, Christians opposed the Jews based on their rejection of Christ. And the animosity over that issue was a two-way street, with each side accusing the other of heresy and blasphemy.

The Ruling of the Council of Nicaea

Let’s return to AD 325 and the Council of Nicaea. What was ultimately established regarding Easter was independence from the Jewish calendar for the sake of church-wide uniformity. Eusebius records a letter from the Roman Emperor Constantine to all those not present at the Council. Keeping in mind the incredible difficulty our modern minds have not seeing racism as a motivation behind disagreements between people groups, let’s review the opening paragraph of the letter:

When the question relative to the sacred festival of Easter arose, it was universally thought that it would be convenient that all should keep the feast on one day; for what could be more beautiful and more desirable, than to see this festival, through which we receive the hope of immortality, celebrated by all with one accord, and in the same manner? It was declared to be particularly unworthy for this, the holiest of all festivals, to follow the custom [the calculation] of the Jews, who had soiled their hands with the most fearful of crimes, and whose minds were blinded. In rejecting their custom, we may transmit to our descendants the legitimate mode of celebrating Easter, which we have observed from the time of the Savior’s Passion to the present day [according to the day of the week]. We ought not, therefore, to have anything in common with the Jews, for the Saviour has shown us another way; our worship follows a more legitimate and more convenient course (the order of the days of the week); and consequently, in unanimously adopting this mode, we desire, dearest brethren, to separate ourselves from the detestable company of the Jews, for it is truly shameful for us to hear them boast that without their direction we could not keep this feast

On the Keeping of Easter, Found in Eusebius, Vita Const., Lib. iii., 18–20.

This is strong language, no doubt. There is clearly a significant disagreement between Jews and Christians, but it is not grounded in racism or ethnicity. Instead, the Church is taking righteous offense at a group of people who were denying Jesus and His resurrection. When we look at this ruling in its historical context and read other literature of the same period where groups of people were in sharp disagreement over religion or politics, we find that this sort of hostile language was par for the course.

Note that the Nicene ruling did not offer any rules for determining the date of Easter. Constantine only wrote that “all our brethren in the East who formerly followed the custom of the Jews are henceforth to celebrate the said most sacred feast of Easter at the same time with the Romans and yourselves [the Church of Alexandria] and all those who have observed Easter from the beginning.” The goal of Nicaea was a unified date of observance for Easter that was untethered from the Jewish calendar. And in that sense, from our modern perspective, I would say that, yes, the Church went too far in its desire to divorce itself from Judaism.

The Proper Date

Today, Easter is observed on the Sunday following the Paschal Full Moon, the first full moon that occurs on or after the March equinox. (And by the way, we don’t use the scientific, astronomical dates of the full moon and the March equinox to calculate Easter, but rather the ecclesiastical dates. Read more here.) But, given the history we just reviewed, what are we to make of the proper date for celebrating Easter today? To me, the early Jewish Christians’ instinct to celebrate the death and resurrection of the Messiah during the Passover makes the most sense. So I would support ecclesiastical reform on the date of Easter being re-connected to the Jewish calendar. Perhaps we consider a hybrid approach that establishes Good Friday on the first Friday following Passover, followed by Easter Sunday?

Therein lies the problem with choosing a “proper” date for Easter. As we’ve seen, an annual celebration is not directed in Scripture. Instead, it grew out of the early Christians’ desire to remember and honor the Resurrection. There is no “right” or “wrong” date on which Easter must be observed. Therefore, being dogmatic on the date seems to me neither wise nor helpful. The particular date we choose to celebrate is far eclipsed by the importance of The Event being celebrated. Consequently, our focus this time of year should be on the victorious work of Christ, our Messiah, Who walked out of His grave that historical Sunday morning, defeating death and sin and reconciling mankind to God the Father.

He is risen, indeed!

Footnotes

[1] The observance was not called “Easter” back then.

[2] Bishops in the early church were not formal authorities like we see today. Rather they were typically the more educated church members chosen from among the community to lead the community. They were considered “first among equals.”

[3] Some would argue, we’re still working them out today.

[4] With the possible exception of Luke.

[5] Except, of course, where those rabbinic writings deny Christ.

[6] The Christian Old Testament is the exact same body of text as the Hebrew Bible, which in Judaism is often called the Tanakh.